Ah, American football. The roar of the crowds. The crunching of bones. The instinctual dopamine rush of identifying with an in-group against a common “enemy.” The blinding splatter of advertisements on everything in sight. Oh, and there’s also the skill and athleticism of professional sportsmen on display, which I guess is appealing.

It’s no wonder that you can’t spit without hitting a football fan in this country and that nothing else on television can compete in the ratings. But we didn’t always have football. The National Football League has only been around since 1920. And in fact, if you pay careful attention to the weird letters that come after the word “Super Bowl,” you’ll notice there have only been 48 of them so far. This isn’t news for the elders among us, but come along with me and let’s explore where this crazy game came from.

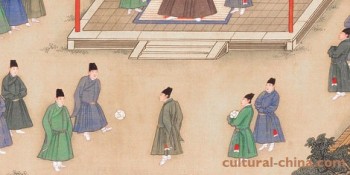

First, let’s go to China. What? I’m serious. It’s likely that the ancient Greeks and Romans played games involving the kicking around of balls as well, but there are actual records of rules (well, instructions anyway) in a Chinese military manual from around the second century BC. The Chinese called the “game” cuju, Chinese for “kick ball,” and it consisted of kicking leather balls through silk hoops placed 9 meters off the ground.

Cuju may not have a national tournament these days, but the Japanese offshoot, called kemari (means the same thing, “kick ball”) still gets played today at Shinto festivals. Kemari is a cooperative sport that looks more like Hacky Sack than anything, where you kick the ball around a circle of players, trying to keep it in the air without using your hands.

Different ball games were played all across the world, from Mesoamerica (we’ll get to the Mayans next week) to Greenland to Australia, but our version’s most distant traceable ancestor comes from England in the ninth century. Back then, whole villages would compete with each other, throwing around balls made of inflated animal bladders, including pig’s bladders (hence the phrase “pigskin”), trying to get them to some landmark or other, like a church or a well. No limits to the number of people playing, and you could use hands, feet, sticks, whatever to get the ball around. They usually played during festivals.

(Some towns still do play on Mardi Gras, called Shrove Tuesday across the pond. The County of Derbyshire holds such matches).

Because every now and again somebody got knifed in the back, say, or perhaps on account of the drunken and disorderly conduct surrounding these outings, several attempts were made to outlaw the sport of football in its early years, though these efforts never seemed to stick. Typically, the penalty for breaking the law would be a fine. I expect if someone tried to ban football today, the NFL could afford to continue playing while paying the fine each week. Heck, that would be a great new source of government revenue! (Note: The author of this article does not advocate or endorse the banning of football in this country, mostly because he does not want to be stabbed with a knife.)

Fast-forward to a school in the town of Rugby (“Rook Fort,” whether referring to the bird or a man’s name) in Warwickshire, England, in 1823. By this time, the game of football had evolved into something a little more organized, with loosely defined rules and a set number of players on the field at a time. Inflated pig bladders were still used, though. The game resembled soccer (itself abbreviated from “association football“), with each side trying to kick the ball into the opponents’ goal. At the Rugby School, a boy named William Webb Ellis was alleged to have received a kick, catching it. The normal response would have been to back up into controlled territory, drop the ball, and try to kick it further downfield. Instead, Ellis said (to himself, I’m sure — and I’m guessing here), “F- this,” and ran forward, ball in hand, thus inventing the game of rugby.

If you’ve ever seen the game of rugby played, it is frantic and violent. I mean, so is American football. But in rugby, each play starts out with the ball in neither team’s control as the opposing teams huddle around it. When the whistle blows, they try to hook the ball with their legs to get possession, and end up creating a terrible mess of potential injury in the process. They call this a “scrum,” short for “scrummage,” which is a form of the word “skirmish,” a military term, which itself derives from an old French word meaning “defend.” More military analogues! Yay!

In the late 19th century, rugby came to North America. For the most part, colleges would compete with each other using eclectic rules that changed from game to game. A coach named Walter Camp was the one who came up with the idea of a line of scrimmage and one team having possession of the ball at the start of plays, along with the need to advance 10 yards within four downs.

Between the start of these new rules and the year 1905, some 300 odd college kids died at football, prompting President Teddy Roosevelt to authorize the agency which would become the NCAA to take charge of streamlining the rules and making play safer. They made forward passing legal, which ultimately changed the game into what we now know as American football.

So what about the Super Bowl? When the American Football League came into the picture in 1960, in direct competition with the NFL, both leagues knew they couldn’t coexist independently. They drained away too much of each other’s audience. So they decided to merge together, and after the 1966 season, they held a grand tournament. But what to call it? The officially designated name, “AFL-NFL World Championship Game,” lacked a certain … kick?

Well, the biggest after-season college football game in those days was held at the Pasadena Rose Bowl Stadium (named after the bowl shape of its stands, which itself took cue from the Yale Bowl stadium), and the name of the game officially became the “Rose Bowl Game” after about 1923. Eventually, all postseason college games became known as bowls. The principal founder of the AFL and coach of its champion Kansas City Chiefs, Lamar Hunt, said he jokingly referred to the game as a “Super Bowl,” because his kids were playing with the bouncy balls called super balls. You know the ones.

So there you have it. The most-watched sporting event in the United States, with all its humble origins. I, for one, think it would have been more fun if everyone from Denver had lined up against everyone from Seattle, trying to get a football to the Seattle Space Needle, last weekend, but maybe that’s just me.