For many of us, daylight saving time has been the norm throughout our whole lives. Spring forward, fall back. A bedrock of how the world conducts its business. In actuality, though, the practice is a recent phenomenon and something of a contentious issue. While there’s little in the way of scientific consensus, several studies show deleterious effects on health and well-being to counteract the gains in retail revenues that come from sliding our schedules twice a year.

First, a bit of background. An hour hasn’t always been an hour. The ancient sundial, for instance, marked time by the passage of the sun, and therefore, the shadows on its face. In the winter, hours were shorter than in summer (an effect which grew more pronounced with increased latitude). Each day had 12 hours, and each night — regardless of which was objectively longer. As clocks became more precise, able to separate hours into equivalent units, midnight and high noon were used as the stable benchmarks, as they consistently happened 12 real hours apart.

Until the industrial revolution(s) around the start of the 20th century, most of the world’s economies were primarily agrarian. Farmers didn’t care what numbers heralded dawn or dusk at any given point in the year; they set their schedule based on the sun. Life was more lax and less regulated. With the introduction of railroads and communication networks, though, timekeeping became something important. Business matters had to be conducted at precise intervals. Shop hours needed to be set and kept. Trains had to leave when they left and arrive when they arrived.

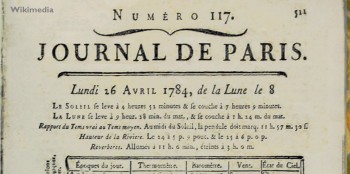

Benjamin Franklin wrote a satirical essay in Paris suggesting that people should wake with the dawn year round to save candles. While the essay offered outlandish ideas such as rationing candles and waking the public at sunrise with cannon fire, the merit of capitalizing on sunshine probably seeped through to modern times in some part from him.

The first individuals to propose a shift in official time for mass use were George Vernon Hudson, an entomologist from New Zealand who wanted more daylight hours to capture bugs, when he published his paper on the subject in 1895, and Londoner William Willett in 1905, who liked to play golf as late as possible. It wasn’t until 1916 in Germany when the idea was made into law, and apart from use during the two world wars in an effort to capitalize on daylight, the United States didn’t make use of daylight saving until the energy crisis of the 1970s.

While Germany was the first state effort to rename the hours of the day, a few myths deal with keeping the sun overhead for longer than normal. In the Old Testament book of Joshua, for instance, the title character takes his Israelite armies on a whirlwind tour of genocide through the lands of Canaan at the behest of Abraham’s God. The residents of one city-state, Gibeon, meet with Joshua under the guise of people from a far-off land, so, you know, they don’t all get murdered out of hand before a bargain is reached. Joshua agrees to ally with them at this meeting, so when he later discovers that, psych!, they’re Canaanites after all, he can’t murder them because he gave them his word he wouldn’t. He just presses them all into slavery instead.

Anyway, a few nearby cities decide that, even if they can’t take on the Israelite army, they’ll pound Gibeon into the ground for making an alliance with the genocidal foreigners, and they march to the attack. Joshua shows up and lays into them, however, and God actually causes the sun to stop moving overhead so the Israelites have more time in the day to beat on the Canaanites. Gotta be thorough about these things.

Another instance of sun-stopping occurs on a bit larger scale. The Celtic god Dagda (Proto-Celtic for “good god,” and perhaps contributes to the Old English dæg, source of “day”) decides to have an affair with the goddess Boann (Old Irish for “white cow,” in the best possible way, I’m sure; shares a root with the word “bovine”), and she gets knocked up. Well, rather than admit what happened or try to be a cuckold, Dagda stops the sun for a whopping nine months, allowing the child to be carried to term in one day. I’m not sure how nobody noticed that such a long freakin’ time had passed at some point, but hey, simpler times, right?

The child, Aengus (Proto-Celtic oino-guss, meaning “one choice”) played his own lingual trick on his old man. When Dagda parceled out his lands among his children, Aengus was away, so he got left out. When he came back, the clever and tricky deity Lugh told Aengus he should ask his father if he could live at Dagda’s own home for láa ogus oidhche, which ambiguously can mean either “a night and a day,” or “night and day.” The latter interpretation was a folksy way of saying “always,” so when Dagda agreed to the terms, Aengus claimed the ancestral homeland for himself, permanently.

So after all that, my question is, if we can just shove time around as we please to take advantage of daylight hours, why can’t we set the clocks way forward in the summer time, say two weeks or so. We don’t need those weeks in March. Who cares about March, anyway? Then shunt them onto the end of November for a nice, end-of-the-year vacation. Who’s with me?