Human religions seem a little obsessed with the idea of a final, conclusive tallying of moral debts and credits. Christians in particular tend to demonstrate a bit of perverse, preemptive schadenfreude over the idea that, when the trumpets sound, some folk (i.e. people we disagree with) are going to the not-happy place, while we, the good ones, are going to have fun in the sun for all eternity. Of course, Christians don’t want sinners to suffer forever, but hey, we can only do so much, right? “So much,” in this case, typically being either handing out vilifying, out-of-touch tracts … or nothing at all. But y’know. Only so much.

The end of the world isn’t just a religious obsession, however. Zombies and nuclear holocausts and plagues have all taken numerous turns in our media. If you’re reading this, you probably live in a relatively safe society (i.e. laws keep bigger people from killing the smaller ones and taking our stuff), even though humans are primed by evolution to use physical force to survive (i.e. kill people and take their stuff); apocalyptic scenarios, no matter how unlikely in reality, are a constant undercurrent in our subconscious awareness. We like to hear stories about desperation and survival in the face of severe adversity, because we want to train ourselves via social learning to survive in those conditions if necessary.

So let’s talk about eschatology for a few minutes. Eschatology (Greek eschatos, “last, furthest, extreme”; logos, “word, being”), literally “word of the end,” refers to the study of the end times as a phenomenon, usually in relation to the biblical book of Revelation (to reveal is to “un-veal,” or unveil), so named on account of the prophecy being revealed to John (a disciple of Jesus and the book’s alleged writer) by an angel on the island of Patmos.

The word revelation is where we get apocalypse (Greek apo, “from”; kalyptein, “cover, conceal”). In the Middle Ages, the word apocalypse was used frequently, not as a catchall for the end times, but with its literal meaning, to discover the truth of something.

Finally, the word Armageddon, which is another of those that is often used in the context of end times, refers to the Palestinian mountain of Megiddo (Har means “mountain,” Megiddo, incidentally, means “place of crowds”), which was specifically mentioned as the site of the final battle in the book of Revelation.

All caught up? Good. Let’s look at what the end of the world is like in Christian, Hindu, and Mayan mythos.

Judgment Day

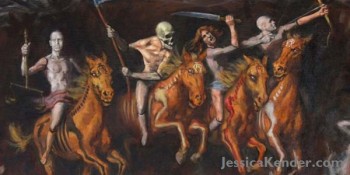

There are several ways religious scholars and lay folk have interpreted the book of Revelation. The most common (as displayed in Tim LeHaye’s unsubtle Left Behind book series) is to assume that the events discussed have yet to occur. It makes sense if you’re trying to interpret the book more or less literally, as it refers to the sun burning up a third of the Earth, dragons roaming about, and the resuscitation of all the dead martyrs. I’m confident in saying that most of that stuff has not, as of yet, happened. Anyway, this interpretation sees the events of the book, even if symbolic, eventually coming to pass. There will be an Antichrist (virtually every major political figure in the Western World has been called thus by some crackpot at one time or another). There will be rapture (good Christian folk zapped up to heaven before bad stuff starts happening). There will be tribulation (wormwood and locusts and the four horsemen). Everyone fights, nobody quits.

Another interpretation is the preterist version, which sees the book as commenting on or foretelling the fall of Jerusalem, which actually occurred circa A.D. 100, when the temple was destroyed and desecrated. Like much of the contemporary apocalyptic literature (none of which made it into the Bible), major use of allegory and metaphor was used to hide the message, so as to avoid unwanted scrutiny by those people the passages were condemning. Think Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. In this interpretation, the long-haired locusts were the barbarian Huns, the whore of Babylon was Rome, and the beast slouching toward Bethlehem was Roman Emperor Nero, who was famous for throwing Christians to the lions whenever he found them.

A third interpretation mostly focuses on a “broad strokes” view of the book, in which God’s people, who find themselves neck deep in troubles, eventually end up pulling through and overcoming adversity. This interpretation sees the book as a metaphor for hope amid times of trial, rather than an account of real events, past or present.

Kali Yuga

Aside from the fact that every Hindu god is an aspect of another god, or has multiple personae, names, and avatars, there are two Kalis, just to add to the confusion. One of them is Shiva’s consort, a bloody warrior woman frequently depicted with sword in one hand and severed head in the other. Her name means “the black one,” from the Sanskrit root kalah, because she existed before there was light. The one they’re talking about in Kali Yuga, however, is a demon who has nothing to do with that other one. Our Kali’s name comes from kad, which means “suffer, grieve, hurt.” He’s basically a bully.

There are four ages (Yuga) in the Hindu mythic chronology, and Kali Yuga is the last one. The bad news is it’s by far the shortest. In fact, it only lasts 1/10,000th of a Brahma day, and it started in about 3100 B.C., at the Kurukshetra War, the one between the Kaurava and Pandava that I talked about in an earlier article. The good news is that 1/10,000th of a Brahma day is still 432,000 of our years, so we’ve got some time yet. Kali Yuga is the age of meanness and pettiness, when people are impolite, greedy, and murderous. Yep, sounds about right. When it’s over, the cycle will start over again with the first of the four ages, where everybody is righteous and wise.

The long count

The Mayans loved their calendars. They were the most accurate calendars ever created, by some accounts, and the culture was so invested in them that they named their children after the day they were born, with names like “Two Monkey” and “Four Death.” They used a method called the calendar round, in which the calendar didn’t reset every year, but rather every 52 years, meaning they didn’t need leap days, or leap seconds, or whatever. Things just rounded out, and the cycle lasted a normal human lifespan. When they needed a longer way to keep track of dates, they used a method called the long count.

So nearing the end of 2012, there was a big to-do about the Mayan calendar ending. Apocalypse! But no, it turns out this was just a misinterpretation of the long count. You see, one day on that calendar is a k’in. Twenty of those is a winal. Eighteen winals is a tun (about one solar year). Twenty tuns is a k’atun. Twenty k’atuns is a b’ak’tun (we’re up to 400 years). December 21, 2012, was simply switching over to the 13th b’ak’tun on the long count calendar. Nothing more, nothing less. No apocalypse. And, you know, there wasn’t one, so it bears out.

So whether the world ends tomorrow, 400,000 years from now, or it’s already happened and we don’t realize it, here’s hoping that we don’t all get eaten by giant, man-faced locusts.