The Supreme Court of the United States made a poor, unpopular decision, and nobody seems to be happy about it. Questions were immediately raised about changing the makeup of the court and amending the Constitution to fix the justices’ huge error. After all, they are an unelected branch of government and an anomaly in our democracy.

You probably assume I’m referring to the Hobby Lobby decision handed down in June. Well, yes, I could be. Or I could be referring to Citizens United, or the Affordable Care Act decision, or Bush v. Gore. Or Roe v. Wade. Or Brown v. Board. Or Plessy v. Ferguson. Or the Dred Scott case. Or Marbury v. Madison. Really, I could be referring to any controversial case from the Supreme Court’s 225-year history. The results are always the same: one side or the other screams bloody murder.

See, hatred of the Supreme Court isn’t a liberal or conservative position. It’s an American position. Hating the Supreme Court is as American as complaining about apple pie on the Internet. It’s part of our DNA, and it dates back to the beginning. And there is a very good reason for that: it’s what some of the nation’s Founding Fathers wanted. I say some because, as I’ve stated before, the Founders didn’t really agree with each other.

To many of the Founders, the Supreme Court was deemed a necessary part of a strong republic because it offered something unique to the system: a strictly legal check on democratic power. The court’s advocates were men who believed in the rule of the majority, but also the rights of the minority.

Then, as now, of course, the minority didn’t mean the downtrodden or the non-whites; it meant the wealthy. Most of the Founders were quite well-off and understood that an unchecked democracy would immediately target the landed elite and lead to their demise. The wealthy couldn’t have that. To many of them, the three primary rights were John Locke’s life, liberty, and property — not the pursuit of happiness, as Thomas Jefferson, publicist in chief, phrased it in the Declaration of Independence.

In fact, it was Jefferson who was the first American president to question the legitimacy and necessity of the Supreme Court. Despite being one of the wealthiest men in the country at the time, Jefferson was an advocate for greater democracy in the young United States. When Jefferson became president, he wielded his power forcefully, despite his previous objections to executive overreach by his two predecessors, and was able to justify it through his belief that he was representing the will of the people.

The Supreme Court during the Jefferson Administration was headed by Chief Justice John Marshall, an appointee of John Adams, a Federalist, and Jefferson’s cousin. The court of the day was still uncertain of its place in the government, and many men who had been offered seats on the bench turned them down in favor of what we would see today as lesser jobs. In Marbury v. Madison, the court had its opportunity to assert its position as a coequal branch of the U.S. government but had to do so in a way that would not offend the president so much that Jefferson might ignore the ruling.

In the landmark case, Marshall ruled in favor of Jefferson’s State Department, led by James Madison, which had refused to deliver credentials to another Adams appointee, William Marbury. Marshall’s ruling was that Madison had indeed acted illegally, but the State Department didn’t have to follow through with the appointment because the provision of the Judiciary Act of 1789 that allowed Marbury to argue his claim before the Supreme Court was actually unconstitutional. The decision established judicial review and made it clear that even the president and his administration had to live under the rule of law, under the arbitration of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Jefferson was less than enthused. He wrote to Abigail Adams in 1804:

“The Constitution … meant that its coordinate branches should be checks on each other. But the opinion which gives to the judges the right to decide what laws are constitutional and what not, not only for themselves in their own sphere of action but for the Legislature and Executive also in their spheres, would make the Judiciary a despotic branch.”

And while Jefferson was the first president to have an issue with one of Marshall’s decisions, he was not the most famous. That would be Andrew Jackson, who responded to the Chief Justice’s decision to side with the Cherokee by completely ignoring it, leading to the Trail of Tears.

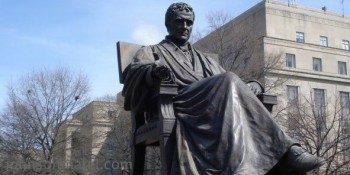

When Marshall died, it was Jackson, ironically, who had the honor of appointing a successor. True to form, Jackson followed the greatest chief justice with probably the worst: Roger Taney. Why was Taney the worst? Well, he made a ruling in a case we know as “Dred Scott.”

You may have heard of Dred Scott, the slave who tried to use the legal system and the Missouri Compromise to gain his freedom. When his case came before the Supreme Court, the justices could have simply decided whether or not Scott was legally bound to his master, but Chief Justice Taney had another idea. Taney wanted to use the case to settle the slavery question once and for all, and he wanted to settle it in favor of slave owners. Taney determined that not only did the federal government have no power to regulate slavery whatsoever, effectively destroying every compromise made since the country’s founding, but that African-Americans, whether slave or free, were not citizens of the United States.

Abraham Lincoln, who was then running for the U.S. Senate against Stephen Douglas, said:

“I have said, in substance, that the Dred Scott decision was, in part, based on assumed historical facts which were not really true … Chief Justice Taney, in delivering the opinion of the majority of the court, insists at great length that negroes were no part of the people who made, or for whom was made, the Declaration of Independence, or the Constitution of the United States.

“On the contrary, Judge Curtis, in his dissenting opinion, shows that in five of the then thirteen states … free negroes were voters, and, in proportion to their numbers, had the same part in making the Constitution that the white people had. He shows this with so much particularity as to leave no doubt of its truth…”

Lincoln was just one of many Americans outraged by the Supreme Court’s incorrect and biased decision. But within eight years, Lincoln would play a huge part in ending slavery in America, and would appoint Taney’s successor as chief justice. With the slaves emancipated through executive means, Lincoln wanted to preempt any questions the court would have about the Emancipation Proclamation and sought to pass a 13th Amendment to the Constitution, guaranteeing the end of slavery in the United States.

In addition to gaining their freedom, black Americans were given citizenship under the 14th Amendment, which also asserted, for the first time, the rights of individual citizens against the governments of the states. New justices on the Supreme Court, particularly John Marshall Harlan, determined that the 14th Amendment incorporated the Bill of Rights onto the states, so that no state government could abridge the rights of free speech, assembly, religion, etc. Before this amendment, if Virginia wanted an established Episcopal Church, the Commonwealth was constitutionally allowed to do so. Despite that intent, in the court’s first opportunities to rule on the new amendment, the Justices decided that, no, the 14th Amendment actually didn’t protect anyone against state governments. Well, except for America’s most valuable people: corporations.

In the Slaughter-House Cases, the court ruled that the “Privileges or Immunities Clause” of the 14th Amendment guaranteed to Americans only the rights offered by national citizenship, not state citizenship. And those rights of national citizenship were very limited. This paved the way for future cases, particularly the Civil Rights Cases, to state that the federal government had no business interfering in the rights of states to discriminate against their own citizens.

The decisions were met with outrage, at least across the north and among Republicans of the time. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, known as the Reconstruction Amendments, were largely deconstructed, except when it came to freedom of contract. While the court claimed it had no power to stop states from discriminating against their own citizens, it did have the power to stop states from trying to regulate their own economies. See, if a business wants to hire someone to work for slave wages, state governments have no right to stop that business — at least according to Lochner v. New York, which saw the court siding with business against people, setting the standard we still see today. So sure, the amendments couldn’t prevent state governments from enacting Jim Crow laws, but they could stop them from enacting minimum wage and maximum workweek laws.

Perhaps the most infuriating thing about these cases is that most are still on the books. The Civil Rights Acts of the Lyndon Johnson Administration had to jump through Constitutional hoops and claim that Congress held the power to enact the new laws under the “Commerce Clause,” as opposed to the 14th Amendment, which is supposed to grant privileges and immunities of citizenship.

Lochner maintained a limited policing power for the federal government and set a precedent that was used by the court to strike down several pieces of New Deal legislation. President Franklin Roosevelt was no fan of the court’s actions, as he made clear in his 1937 State of the Union Address:

“The Judicial branch also is asked by the people to do its part in making democracy successful. We do not ask the Courts to call nonexistent powers into being, but we have a right to expect that conceded powers or those legitimately implied shall be made effective instruments for the common good.”

But following FDR’s landslide reelection victory in 1936, the court’s opinion seemed to change. West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish saw two justices alter their usual judicial stance and allow a Washington state minimum wage law to remain in effect. Many believe the two justices made the change in order to prevent Roosevelt from enacting his so-called “court-packing plan,” which called for the membership of the Supreme Court to change from nine to 15.

Essentially, FDR was the first President since Jackson to successfully counter the Supreme Court, and he did it without using Jackson’s hilariously illegal means of just ignoring them. But the Supreme Court is supposed to be a bit antagonistic toward the president and Congress. It exists to balance out the power of the government so that even those who write and execute the laws are subject to them. And the president and the Senate get a say in who serves on the court in the first place.

Of course, presidential appointments don’t usually change judicial philosophies of the court overnight. In fact, the idea of lifetime appointments was that the previous generation of leaders would continue to hold some sway over the current. These appointees would last for about a generation before the president could choose a replacement. Ronald Reagan, however, changed the game by appointing very young justices to the court, allowing his appointments to affect American law for much longer than had been standard. His successors have followed the pattern, with George W. Bush’s appointment for chief justice, John Roberts, being young enough to almost guarantee him another two decades at the court’s head.

And the Roberts Court continues the long-held American tradition of frustrating a large percentage of the population. Ultimately, the court is a good thing, but it is easy to see why people are calling for changes in the system. Citizens United and the Hobby Lobby case have opened the floodgates to potentially dangerous changes in American governance. Or, they could be what finally causes some things in the country to change for the better. Only time will tell.

But until then, don’t be shocked the next time the Supreme Court does something that you find infuriating. After all, it is what (some of) the Founders intended.