Poor rosé. Recent decades have not been kind to the pale wine, due in large part to that dreaded enemy of serious winos everywhere, White Zinfandel. But rosé has a long history in the wine world, from its heights as the premier wine of the Western world to its lamentable current position as merely an afterthought.

Rosé wines are, for the most part, actually red wines. In all red winemaking, grapes are crushed and the juice is allowed to rest in a tank with the broken skins; this mixture of juice and skins is called “must.” The juice pulls flavors and colors from the broken skins during maceration. After a period of time determined by the winemaker, the must is pressed, and the skins discarded. Here’s the key: how long the juice is in contact with the skins determines whether the wine will be red or rosé: The less time, the paler the rosé; the more time, the deeper the red.

(The solid parts of the must, called “pomace,” are sometimes reused in certain brandies, including grappa.)

Believe it or not, rosé was actually the preferred style of wine for centuries. The Greeks and Romans both allowed minimal grape skin contact time. Winemaking technology was primitive, and when red wines were attempted, they were often harsh or bitter. Instead, grapes were crushed by hand (or rather, by foot) and juice was drained off the skins almost immediately, creating a pale pink wine. This practice continued for centuries, well into the Middle Ages. During England’s Elizabethan Era, pale “clarets” (the British term for Bordeaux vintages) were the preferred wine.

As techniques advanced, rosé was forced to share the limelight with powerful reds. The tipping point for rosés came after World War II. Two Portuguese wineries began producing popular, sweet, sparkling rosés. At the same time, white wine was surging in demand, and California wineries found themselves flush with red wine grapes. California vintners began making sweeter “white” wines from red wine grapes, using minimal skin contact time. This gave birth to the generic term “blush” in the 1970s, as well as to Sutter Home’s infamous White Zinfandel.

Americans who didn’t normally drink wine gravitated toward the sweet White Zinfandels, so some wineries began to copy that style in their rosé offerings. Wines labeled rosé became confusing — was the bottle going to be sweet or dry? Eventually, “serious” wine drinkers gave up on rosé, especially in America, assuming that most would be too sweet, and they stuck to dry reds and whites.

During the last decade, however, high quality rosé has seen a resurgence. Perhaps those novice wine drinkers of the 70s and 80s have finally grown up, or perhaps more adventurous drinkers are willing to take a chance on the pale wine. Whatever the reason, in 2010 alone, U.S. retail sales of imported rosés of $12 or more increased by almost 20 percent in volume, a rate of growth well ahead of total table wines.

So where should you start exploring this reinvigorated segment of the wine industry? France, naturally, and Provence in particular. Provence, on the southeast Mediterranean coast, has been, and continues to be, the standard-bearer of rosé wine worldwide. It is one of the few regions on Earth that produces more rosé than red or white. And why not? The traditional cuisine of the region, full of fish and fresh vegetables, is a perfect match for light bodied, fruit-forward, acidic, dry and off-dry rosés.

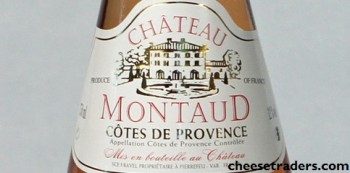

Chateau Montaud is a fantastic example. At $10 to $12, the wine is inexpensive and has terrific strawberry, cherry, and herbal flavors, with hints of melon and tart apple. The zingy acidity makes it food-friendly, especially with light appetizers or cheeses, salmon, and shellfish. It’s really refreshing and is my go-to rosé.

Elsewhere in France, the Tavel appellation along the Rhône River (in the Côtes du Rhône) is another prominent rosé region. Tavel wines are 100 percent rosé: no reds or whites are allowed to be produced. Some wineries here drain part of the must off the skins early, after only 12 to 24 hours, while the rest is left to macerate longer, imparting more powerful flavors. These two batches are then blended together to create rosés with higher alcohol content (up to 13.5 percent), darker coloring, and more intense flavors. (Contrast the light bodied rosés from Provence with these full-bodied offerings.)

Check out the Domaine des Carteresses Rosé, for around $12 or $13. The color is a far deeper pink than the Chateau Montaud, with a level of intensity more like a light-bodied red wine. On the palate, you’ll find watermelon, red berries, grapefruit, and tart apple characteristics and a clean mineral finish. (Try it with chicken barbecue.)

Most French wines are blends of multiple grape varieties, and French rosés are no exception. Both Provence and Tavel winemakers primarily blend Grenache, Mouvedre, Syrah, and Cinsault grapes in their rosés.

There are, of course, plenty of other options when purchasing rosé from elsewhere in Europe and in the United States. Outside of France, the regions of Navarra and Rioja in Northern Spain make delicious rosados — though rosé is not the big focus there as it is in Provence and Tavel. In my earlier column about Finger Lakes wine, for example, I mentioned that wineries in that region make rosés, and I have purchased quite a few — though I did have the chance to taste them first, which I recommend.

Be warned that rosé is sometimes an afterthought for wineries. The best red wine grapes go to the red wines, leaving lesser quality grapes for rosés. Some other wine regions in France use the saignée method: draining some juice off the skins after limited contact and bottling it as a rosé, while leaving the rest of the juice on the skins to make a more powerful red wine. And let’s be clear with this method: the red wine is the true focus; the rosé is bottled quick and cheap for short-term income, while the red ages in barrels for months or years before bottling.

Personally, I’d rather drink a rosé that was the focus of the winemaker, which is why I mentioned Provence and Tavel. Bottom line: unless you have a chance to taste before you buy, try a rosé from a region known for the style — and dump that White Zinfandel bottle. For a picnic or hot summer day, a dry rosé is tough to beat.