Winter has officially worn out its welcome. Yes, yes, I know that this winter has so far been warmer than the average recorded, and climate change, and it’s just my perception based on recent experience here in south-central Pennsylvania, but still. I don’t like being cold.

Of course, almost as soon as the cold goes away, we get the heat. It feels like the mild seasons, spring and fall, are only shadows of the more extreme seasons, wistful and fleeting. In fact, not all cultures have four seasons like we do in North America. Tropical climates have two: the hot season and the wet season. So why do we even use four? Where does that come from?

There are, of course, two solstices (Latin: “still sun”), so named because those are the dates when the sun reaches its visible apex in the sky during summer and its nadir in the sky during winter as the Earth rotates on its tilted axis. The two equinoxes (Latin: “equal night”), so named because those are the days when the night and day are the same length (though that’s not quite scientifically true), occur in between the solstices on either side; they are the vernal (which is just a Latin and Norse term for the season of spring) and the autumnal (Latin and Old French term that potentially shares a root, auq, with the word August, meaning “drying up season”).

The seasons don’t actually begin on the solstices and equinoxes, though, because it takes a few months before the actual weather begins to change in relation to the prolonged/shortened exposure to the sun. Sort of like how outdoor pools don’t warm up at noon, but in the afternoon after the sun has been shining on it for a few hours. The atmosphere works somewhat similarly, but on a much greater scale.

“Spring” comes from an Old English word (springen) meaning to leap, burst forth, or fly up. It began to be used in relation to the seasonal change in the 16th century, in a descriptive sense, as in “spring of the year.” Before that, the word “lent” was used to indicate the season, from Old English/Middle Dutch, meaning “length,” as in lengthening of the days, along with printemps, French for “first time.” Spring is the season when plants spring up, and the sun springs above the horizon earlier and earlier. Representing change and birth and optimism, it’s usually considered the “first” season of the cycle.

“Summer” seems to come from an ancient Sanskrit form (sama), meaning “half year” or “season.” Far enough back, people would have used two seasons, the warm and the cold, and summer was one half of the year. The other season was — well, we’ll get to that.

“Fall” comes from Old English as well (feallan), meaning to fail, decay, and die. It also found usage in relation to the season in the 16th century, both as an antonym to spring and because it’s the season when things fail, decay, and die.

“Winter” means, roughly, “white year” from Proto-Indo-European and Celtic words (wind/vindo). So summer was “half year” and winter was “white year.” I’m not sure if there was originally a subtle distinction in the language, like “regular half year” versus “white half year,” but it seems likely, to the extent that the words share a root language. Summer and winter originated well before spring and fall — as seasons, at least.

Now that we know something about where the idea of seasons and their names came from, let’s figure out who these ancient people blamed for the cold. And before you start to think these myths are silly, ask yourself how much stock you, or people you know, put in the predictions of a groundhog on these matters.

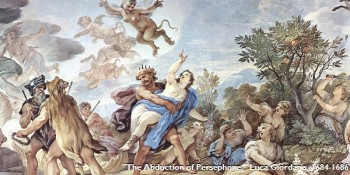

Demeter and Persephone

These two Greek harvest and nature goddesses, mother and daughter, whose worship predates that of Zeus and his cohort (though Zeus is also supposed to be Persephone’s father), kept everything bountiful and sunny, year-round. One day, Hades, god of the underworld (and Persephone’s uncle), kidnapped Persephone ‘cuz she was pretty. Creeeeeper. Demeter flipped out and went into mourning, causing the land to turn bitter cold and dry up. Naturally, Zeus intervenes.

“Hades,” he says. “What in tarnation is you doin’ wit’ mah youngun.” (I like to imagine the Olympians as inbred mountain folk, for obvious reasons.)

“She et six seeds from a pomegranate. She’s mah wife now.”

“Dag nabbit. If’n it’s only six seeds, you only get ‘er fer six months.”

So Demeter makes “summer” happen half the year, when she has her daughter around, and “winter” when Persephone’s in Hades.

Inanna and Dumuzi

The Sumerian goddess of the sun decided she wanted to check out the underworld, where her sister Ereshkigal, keeper of the dead, lived. They weren’t close, and Inanna was probably just going there to brag about how great things were on the surface. She got told by gatekeeper after gatekeeper that she had to give up her items of power, like her wand and her headdress and necklace, to pass, so she did (for some reason). When she finally got to her sister, Erishkigal killed her immediately. Once again, no more sun meant no more summer, so Enki, leader of the pantheon, sent some servants in to go fish her out and bring her back to life.

Erishkigal said, “No fair, send someone to replace you.”

Inanna looked around and found her husband, Dumuzi, lounging about, not in mourning but living it up bachelor style, so she said, “Yeah, he’ll do.”

Dumuzi’s sister offered to take his place in the underworld for half the year, and Inanna, conflicted about her feelings, still mourned for him for the half of the year when he was down there, causing winter.

Amaterasu

The sun goddess (kami) of Japan, Amaterasu, got ticked off at her brother, Susanoo, flaying ponies and throwing them at her loom, so she hid in the cave, Amano-Iwato, leaving the world in darkness. The other gods showed up and begged her to come out, to no avail. Finally, Uzume danced around naked, which caused the male gods present to laugh (for some reason?), and that drew Amaterasu out of the cave.

Uzume had put a mirror at the mouth, which stunned Amaterasu long enough for some other gods to block the way back in. They made her shine her light again and, eventually, she and Susanoo made amends, sort of. While this myth doesn’t directly mention the seasons, it’s easy to see that the sun has some volatility in how she behaves.

So, while the ancient myths have more death (and pony-flaying) in them compared to our Groundhog Day, I’m sure there’s more than a few people who’d like to take a hunting rifle out to Punxsutawney and change that score. Gotta blame winter weather on somebody, after all.