After seeing Captain America: The Winter Soldier with friends, we spent some time discussing how well Marvel has done creating the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and how well they’ve adapted the various Avengers heroes. This led to a discussion about some other comic book films that were much more disappointing. At the top of my list: X-Men: The Last Stand.

To give you some context: I am a big X-Men fan. Prior to the creation of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, I would say the X-Men were probably my favorite Marvel characters. I confess that I have not read every issue of every X-related series — though I would love to someday. However, when I was in elementary school, I frequently borrowed comics from a friend, and we would often get into debates about who was the coolest X-Man. We would also fantasize about our dream casting for an X-Men movie, if one were ever made. (I’m pretty sure Patrick Stewart is the only actor from our list who actually made it into a film, but come on, who else would you cast as Charles Xavier?)

X-Men finally made it to movie theaters about six years after the height of my comic book craze, but I was still excited to see my favorite heroes on the big screen. I was so excited that I was willing to give the creators the benefit of the doubt and forgive them for things like altering Wolverine’s height (because Hugh Jackman), excluding Beast and Angel from that first movie while making Iceman much younger than Cyclops or Jean Grey despite the fact they were all founding members of the team, and pretty much everything about Anna Paquin. (I’m sorry, I have nothing against Paquin — she is terrific in True Blood — but Paquin in the role of Rogue, a character I love, just bothers me).

Despite these complaints, I really enjoyed the first film, and X2 wasn’t bad either. In fact, I got really excited at the end of the second movie, because I recognized they were setting the stage for the Phoenix to appear in the third film. At the time, I had no idea which incarnation of the Phoenix we would see, but I was looking forward to watching what was arguably one of the best X-Men storylines ever written translated to the big screen.

If you’ve been following my column, you may recall a few weeks ago when I wrote about trying to judge books and movies separately lest you be inevitably unhappy with every film adaptation. Perhaps if I had taken my own advice while watching X-Men 3, I wouldn’t have been nearly as disappointed. Then again, The Last Stand is more likely one of those exceptions that I just can’t forgive.

After viewing The Last Stand, I remember leaving the theater with my brother, both of us extremely disappointed with the film. One of his comments was that it was a great action film about people with superpowers, but it was not a good X-Men movie. I’m inclined to agree.

X3 tramples all over the X-Men lore that laid the groundwork for the films to be made in the first place. I was very frustrated that the writers killed Professor X and, even more so, Cyclops. The field leader of the team — the one who is supposed to actually outlive Jean, many times, in the comics — gets killed off-screen early in the movie with very little fanfare. But my real problem with the film was in how it handled the Dark Phoenix storyline — or more like how it didn’t handle it.

As I stated earlier, I haven’t read all the X-Men comics, and at the time I first saw X3, I hadn’t read “The Dark Phoenix Saga.” Nonetheless, I was pretty familiar with the general plot and knew that what they had shown in the film was not anything close to the original story. After reading the actual comics, I only got more frustrated with the liberties the film took.

I understand that the entire Phoenix storyline, from the time Jean Grey became the Phoenix until she died, encompasses several years’ worth of comics. It’s not an arc that could easily be told in a single film. I even understand going straight to Dark Phoenix and never showing us the good side of the Phoenix power. The problem lies in the fact that it seems like director Brett Ratner and the screenwriters only wanted an all-powerful weapon for Magneto to wield so they shoehorned Dark Phoenix into that role.

Jean Grey’s death in X2 and resurrection as the Phoenix in X3 are very similar to the story described in Uncanny X-Men issue no. 101, only instead of taking on radiation while landing a spacecraft as in the comics, Jean sacrifices herself while trying to hold back a flood long enough for her friends to take off in the Blackbird. This is the only way in which it feels like the film’s producers were attempting to incorporate anything from the original storyline into the movies.

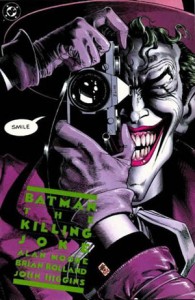

Dark Phoenix was an incredibly powerful being. As The Watcher says at the end of Uncanny X-Men issue no. 137, “She had only to think, and that thought would become instant reality.” In the comics, Dark Phoenix is a force of nature; she wields limitless power and is perfectly aware of how to use that power. She consumes stars and destroys worlds in order to feed this power; she’s nearly unstoppable. Yet, in X-Men 3, she is made subservient.

Dark Phoenix kills Xavier because she thinks the Professor is trying to control her, but then she turns and allows Magneto to actually manipulate and control her. Despite being the most powerful mutant in Magneto’s arsenal, Phoenix spends most of the final battle observing before she begins to unleash her full strength, only after Magneto has been neutralized. While in the comics she is completely independent and a threat in her own right, in the films she needs to have someone to follow.

Perhaps one of most controversial changes to the storyline — and the part that bothered me the most — is the death of Dark Phoenix. In the original comic, the X-Men temporarily subdue Dark Phoenix using a device created by the Beast. Jean gains control of herself for a brief moment and she begs Wolverine to kill her, but he hesitates and Dark Phoenix once again takes over. Near the end of Uncanny X-Men no. 136, Xavier engages in a psychic battle with Dark Phoenix and, with the help of Jean’s suppressed consciousness, is able to build up a wall around Dark Phoenix in Jean’s mind, suppressing the malevolent entity. However, the Professor’s solution is not permanent: Dark Phoenix begins to reemerge in the next issue. This time, before Jean completely loses control, she takes her own life in order to save the lives of her friends and the universe.

Jean Grey’s sacrifice is the ultimate depiction of love and strength. Instead of once again becoming Dark Phoenix and being responsible for countless more deaths, Jean takes control of her destiny and chooses to defeat the evil within no matter the cost. However, in the on-screen version, Jean was robbed of this noble act. Instead, Jean dies at the hands (claws?) of Wolverine, thus taking a strong and noble act of female empowerment and turning it into another example of male dominance.

This effect may have been unintentional on the part of the writers. I’m sure this ending was chosen for its drama, but the change still sends the message that Jean, though able to kill anyone with no more than a thought, is not strong enough to defeat Dark Phoenix. She needs someone else to do it for her, and that someone just happens to be one of the most masculine characters in the movie.

Another problem I have with this sequence of events is the focus on Wolverine in general. I understand that Wolverine had become the breakout star of the X-Men franchise, and don’t get me wrong: I like Wolverine and I love Jackman. But Wolverine has become the face of the X-Men and the star of these films, and that simply shouldn’t be the case. The X-Men are, first and foremost, a team, and no one character should stand out more than any other. If anyone should receive top billing, it is the leader of the team: Cyclops. This shift in emphasis to Wolverine added to my frustration that Cyclops was killed within the first half hour of the third movie and, consequently, doesn’t even appear in the final battle.

Basically, Dark Phoenix is used as a subplot in this film, taking a backseat to the mutant cure storyline, which seems like a huge waste of one of the best arcs in Marvel history. “The Dark Phoenix Saga” did not receive the attention or focus it deserved in this film, and probably shouldn’t have been squeezed into the story at all. Imagine the separate compelling, blockbuster film series that could have been developed with proper treatment of the saga.

As my colleague John has elaborated on in his defense of X-Men: The Last Stand, the film had some good moments. (Kelsey Grammer as the Beast is one of the best parts of the movie.) In fact, if you were to take the Dark Phoenix storyline out of the movie entirely, it probably would have been decent, and I certainly would have enjoyed it more. The final battle sequence was well done, and I enjoyed the fight between Iceman and Pyro — particularly the moment when Iceman finally becomes the completely frozen version of himself.

Needless to say, X-Men: The Last Stand was a huge letdown for me. However, X-Men: First Class restored some of my faith in the franchise, and I’m cautiously optimistic that X-Men: Days of Future Past — despite the decision to once again put Wolverine front and center, taking over Kitty Pryde’s role in the original storyline — will not disappoint.