Many of us were able to spend yesterday with family and friends, eating ham and potatoes and deviled eggs that mom (or another varied matronly figure) cooked up for the occasion. Some of us attended our local place of Christian worship in honor of the death and resurrection of Jesus (Yeshua), while others refrained.

Certainly, the Christian church (fragmented though it be) is the primary sponsor of this particular day of rest — which makes it so odd that it’s named after what is almost certainly a pre-Christian, Saxon fertility goddess, Ēostre. It’s sort of like if I created my own religion (like Scientology … but we’ll call it “Give-Jim-all-your-money-ism”), and then decided the biggest holy day of the year, the celebration of when … uh … Supergod ate all the alien bad guys 5 billion years ago … anyway, that day should be called “Buddha.”

To be fair, the early church didn’t start off calling the day “Easter.” In fact, it wasn’t even just one day (it still isn’t), but a whole week, from Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday, called then (and now, in most of the rest of the world) “Paschal,” which is a Latin derivation of the Hebrew Pesach, or “Passover.” Passover is the traditional Jewish holiday celebrating the time when God killed all the first-born Egyptian sons because the Pharaoh wouldn’t let Moses’ people go. The Jews were “passed over” because they sacrificed goats and smeared the blood on their front doors.

This event is one of the most visceral representations of the idea that the Hebraic God’s people can be saved (or forgiven, or redeemed) by offering up a blood sacrifice that runs throughout the Old Testament. Since the whole notion of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross ties directly into that, the early Christians decided to just steal the whole holiday: word, time of year, ritual, and theme, whole hat from the Jews (again, to be fair, they technically were Jews themselves … as are Christians, arguably, today — just an extremely “reformed” version).

So if the day already had a perfectly good, if plagiarized, name, why give it a totally different one in English? Simply put, when the Roman Empire started to spread Christianity to the Germans and the Bretons in the early hundreds A.D., those cultures already had an early spring celebration called Ēosturmōna? (“Easter month”). This was the big-deal celebration around those parts, and even if people were willing to be bullied into monotheism and whatnot, they weren’t willing to give up their annual “We survived the winter, now let’s get bizzay” traditions. So the name stayed.

But what do we know about Ēostre anyway? Not that much. There was an 8th-century account by a canonized monk named Bede attesting that the holiday of Easter Month was once used to celebrate a goddess, but that’s the oldest bit of writing available on the subject. It could possibly be that no such goddess had ever existed, and the Breton tribes used the word “Easter” to refer to the dawn (from Proto-Indo-European root aus, “to shine,” shared by the word “east”), and, therefore, to spring, since, y’know, dawn starts happening sooner in spring.

On the other hand, the dawn/fertility goddess of the contemporary Old High Germanic tribes was named Ostara, and there is a lot of evidence to suggest that many fertility goddesses, from Roman Venus to Babylonian Ishtar to Sumerian Inanna, all derive from a root goddess named something like “Hausōs,” the personification of dawn. It seems likely that the nearby Northumbrians in England would have taken the dawn goddess along with the other deities intrinsic to these cultures.

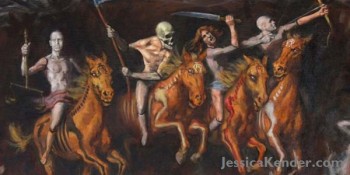

In the root mythology, Hausōs was a bringer of light who was punished for aiding humanity (much like Christian Lucifer and Greek Prometheus, but unlike Japanese Amaterasu). Typically, the goddess is imprisoned by a dragon or another god and gets rescued by a powerful hero, either another god or a mortal. This, of course, symbolizes the day/night cycle on Earth.

While we’re on the subject of Easter, a quick note or two about bunnies and eggs. Are they really just fertility symbols co-opted by Christians to represent resurrection? Well … maybe, maybe not. One popular theory about dyed eggs is that people had to hard-boil them to preserve them during Lent, when they weren’t allowed to eat them, and frequently put flowers into the pot to color the eggs to make them pretty. Then, the eggs were a treat on Easter Sunday.

As to the bunny, there was a peculiar belief in medieval times that hares were hermaphroditic and able to conceive without losing their virginity. Thus, the idea of the hare was linked to the virgin birth and showed up in illuminated manuscripts and paintings of Mary and the Christ child. That, however, has nothing in particular to do with death and/or resurrection, so it’s anyone’s guess how the Easter Bunny specifically landed the job.

Hope you all had a pleasant “East Day,” and feel free to consider joining the church of Give-Jim-all-your-moneyism. New members are welcome anytime.