In a previous Nerd/Wise article, I explained why comic books and graphic novels are unfairly criticized and should be viewed as a form of modern art and literature. That discussion was limited to more unique works in graphic literature, ignoring the superhero genre that has come to define the medium. Today, we give superheroes their due by looking at how they can be used to tell complex, real stories. Specifically, we look at the X-Men and the allegory of civil rights, starting with its allusions to the African-American Civil Rights Movement and moving on to today’s references to the push for LGBT rights.

In 1963, Stan Lee, legendary creator of almost all of our most famous heroes, was running thin on ideas for origin stories and, in a bout of laziness, decided to create a team of heroes who were simply born with their powers. Ironically, this decision created the most compelling trait ever tacked onto a superhero team. The X-Men were heroes, like Spider-Man, because they chose to be, and chose to use their gifts for the betterment of mankind. Unlike Superman, they weren’t deified and honored but marginalized and feared.

Since (Uncanny) X-Men #1, this has been what makes the X heroes unique. They didn’t ask for their gifts, but they have to deal with them. And as such, they became the stand-in for every person who has ever felt marginalized for traits beyond their control, whether it be skin tone, gender, or sexual orientation.

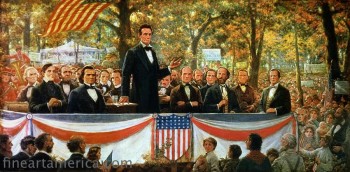

The real world shows us that it is difficult to come to terms with the qualities we bear for which society chooses to judge us. Some of us are unable to handle this pressure, and we seek an outlet for our frustration. Sometimes, that frustration is let out through art or music, but many times, it can lead to outbursts of violence. Those of us who feel marginalized need the guidance of those who relate and understand our problems and can offer direction. In the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, the African-American community chose a leader in Martin Luther King Jr. The X-Men were given Professor Charles Xavier.

Professor X, the mentor and leader of the X-Men, faced discrimination his entire life — not necessarily for being a mutant, which he could easily hide, but for being a quadriplegic. Professor Xavier, like King, was proof that an educated man with a vision could make a difference. Both men guided the marginalized, gave value to the voices of the unheard, and spoke truth to power while offering a vision of peace. Obviously, there are some differences. King never trained the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to fight giant robots bent on his peoples’ destruction in the streets of New York, but the similarities are still worth noting.

On the other side of the coin exists Magneto, who, for most of his history in the comic books, was the leader of the Brotherhood of (Evil) Mutants. While Professor X appealed to the better angels of our nature, Magneto appealed to the more likely response from people who have spent their lives oppressed and hated. Magneto, as leader of the Brotherhood, offered mutants a chance to retaliate against human hatred. Instead of pushing his followers to win over the hearts and minds of humanity, Magneto told them they were superior, they were ascendent, they were meant to replace homo sapiens.

Magneto began as a more simplistic villain, even outright calling the Brotherhood “evil,” but he eventually evolved into a nuanced and accessible character, thanks primarily to the tremendous work of X-Men godfather Chris Claremont. Magneto was revealed to be a Holocaust survivor, and his hatred of humanity can be better understood in this light. He has already seen what humans will do to the “other,” and he refuses to allow it to happen again.

It’s easy to see the appeal of Magneto’s message — except for the mass genocide parts, at least. Magneto’s later characterizations, including those beautifully portrayed on the silver screen by Ian McKellen and Michael Fassbender, show him as a militant mutant advocate but not an inherently evil man. He appeals to the young men and women who are sick of the status quo and see that the entire system is flawed and biased against them. To them, the problem can not be fixed through gradual change and education but by tearing the whole system down. Philosophically, this isn’t necessarily wrong; sometimes, a revolution is necessary to fix humanity’s mistakes. The problem is when this is taken to its logical extreme and philosophy begets violence.

Magneto has been compared to Malcolm X for his “by any means necessary” approach. Perhaps this is unfair to the man and to the character, but it is obvious that Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, and the Nation of Islam at least inspired much of Magneto and the Brotherhood’s characterization. The militancy, the rhetoric, and the desire to separate mutantkind from humanity are lifted from the Nation of Islam and their push for separation of the races.

The X team has historically been very diverse. Since Giant-Size X-Men #1, the team has had an international flavor. Joining Scott Summers and Jean Grey were the Canadian Wolverine, the German Nightcrawler, the Soviet Colossus (in the middle of the Cold War), and Storm, who was born in New York City but raised on the African continent.

This second X team was introduced in 1975, when even including an African-American superhero was still controversial. Even more unique was that Storm’s character was not defined by her “blackness”; she was a character in her own right, with an interesting origin story and traits unique to her — something incredibly rare for a woman superhero, let alone a black woman superhero.

Despite the team’s ethnic diversity, Xavier’s new gang of uncanny heroes often dealt with problems more appropriate for a cosmic opera than a civil rights allegory. However, Claremont’s skills as X-Men writer knew no bounds, and he managed to create an enduring story that appealed to fans of both science fiction and political allegory.

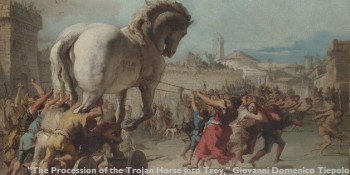

The upcoming X-Men movie, Days of Future Past, is based on the comic book of the same name about a dystopian future in which mutants have been hunted down and placed in internment camps. The story is the realization of Magneto’s nightmare: a second holocaust for his people. The Sentinels, giant mutant-hunting robots, seek out the former X-Men and capture or murder them ruthlessly, strictly because of their X-gene. This potential future is a reminder of everything the X-Men have to fight against. They are being destroyed strictly for being different, like the Jews of the 1930s and 40s. They are feared without reason, like many of those put through the communist trials of the early Cold War era.

And this future seems very possible in the comic book world Marvel had created by 1980. The mutants were being marginalized since their kind had first been known to the world. They had been called “mutie” and attacked by mobs. Despite doing everything right, they never seemed to make much progress.

The X-Men have evolved over the years and have taken on the characteristics of each new group being marginalized by the American mainstream. At times, they are derided as enemies of God and demons incarnate, corrupting society with their sinful ways, like the LGBT community of today. They’ve been told to stay in the closet about their powers and asked to simply “stop being a mutant,” like Iceman was in X2. And in Joss Whedon’s “Gifted” story line, scientists created a “cure,” to which the mutant community asked, “Does that mean we have a disease?”

Since 9/11, the X-Men have taken on the burden shared by Muslim-Americans. Should they be judged for the errors of others? Should all Muslims be feared and marginalized because of a few extremists? Should good, tax-paying mutants be feared and marginalized because of a few mutant terrorists?

The X-Men teach us about ourselves. They bring into focus our fears and our prejudices and ask us to rethink what we claim to already know. They show us that the world isn’t always black and white, even in a medium that was built on black and white morality tales. Are the X-Men perfect? No. They make mistakes. Often tragic ones. And many times, their dealings with the government create morally ambiguous situations in which we are left to believe that both sides are right. They challenge us. Hopefully, they continue to do so, and future generations can find themselves questioning their world thanks to the brilliant stories told about the Uncanny X-Men.