The first of April was last Tuesday, and as always, you could find plenty of people playing tricks (if mostly just on Facebook), and others falling for them, no matter how obvious.

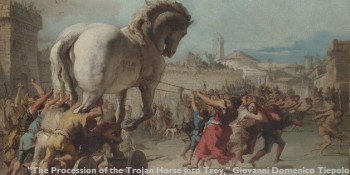

The traditional, time-honored prank of the day is to send someone on a fruitless errand, as in Scotland, where the day is called “Hunt-the-Gowk Day” (gowk is a Scots word for “cuckoo”). Much like the grand Boy Scouts prank of “snipe hunting,” a Scot might send a younger one across town to a friend’s house with an “urgent” message, to be opened only by him/her. The message, of course, reads, “Dinnae laugh, dinnae smile, hunt the gowk another mile.” Later, the “hunters” would share laughs over which messenger took the longest to realize he was being played.

But where does this traditional day of pulling one over come from? It’s something of a mystery, with many potential origins sounding like April Fools’ Day pranks themselves (and one origin story is admitted to have been just that).

It may have stemmed from the long ancient time of mythological Noah (whose amazing true story has recently been made into a full-length motion picture, or so I’m told), who released a dove on the first day of spring, before the water had receded, to see if it could find land.

Or it might come from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (specifically “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale“) in 1392, in which the title character is tricked by a fox on the 32nd day “syn March bigan” (since March began), which was later considered a typo.

In 1983, a history professor named Joseph Boskin claimed to have traced the practice to the era of Constantine, when the emperor made a jester the ruler of his empire for a day. Boskin then revealed that this “new origin story” was itself an April Fools’ Day prank, and the newspapers retracted their stories.

Most likely, however, the practice comes from France in 1582, when the French adopted the Gregorian calendar, which made January 1 the start of the new year. The older practice of beginning the year on April 1 was still kept in many rural areas, and the city folk mocked and derided these people as “April fish” (poisson d’Avril), since fish in early spring were easier to catch. Today, a common prank in France is to tape a paper fish onto a victim’s back (much like a “kick me” sign).

The word “April” means “(month) of Venus,” or Aphrodite in Greek. The trickster Mercury doesn’t get his own month, or he might be a better fit for it. Indeed, while pretty much every culture celebrates a day of general foolery, it’s only in polytheistic religions that we typically find gods specifically devoted to trickery and cleverness. Certainly the closest we get from the Christian God is adherents who like to say “God has a sense of humor” when unexpected things happen.

Trickster gods, by comparison, are allowed to have multiple facets, sometimes good, sometimes evil. They tend to give humans things they “shouldn’t” have and get in trouble from their own paranoia and from double crosses (just like some April foolers). Two of the more interesting trickster gods are Anansi and Wisakedjak.

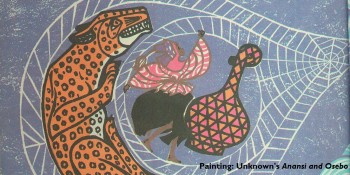

Anansi (Akan for “spider”) is a West African spider god and the god of all stories. Sometimes, he’s the one who hoodwinks the other gods, and sometimes he gets his comeuppance, but he’s generally known for his cleverness, using the brute strength and vanity of his fellows against them. In the United States, many of his stories were retold under the moniker “Br’er Rabbit.”

The great spider became the god of stories when he brought the python, the leopard, the hornets, and the dwarf to the sky god Nyame. Anansi tricked the python by betting him to see whether a branch was longer than the snake, and that Anansi had to tie the snake to the branch to measure for certain. The leopard Anansi tricked into a hole, then offered to use his web to help the leopard out, and so snared him. Anansi poured water on the hornets’ nest and told the bees it was raining, then tricked them into a pot, saying it would keep them dry. Finally, Anansi made a sticky doll and put it, with a yam, next to the Tree of Life. When the dwarf stopped by and ate the yam, she tried to thank the doll — and angrily struck it when it did not respond, getting stuck.

Wisakedjak (sometimes anglicized to “Whiskey Jack”) was a Cree and Algonquin hero god related to rabbits who loved teaching and playing tricks, up to and including burning his own buttocks to teach them not to fart while he’s hunting. In some instances, he even outwits the fox and coyote, notoriously clever animals. In one story, Wisakedjak was hungry, so he tricked a group of ducks into a bag filled with music and convinced them to dance with their eyes shut while he wrung their necks one at a time. In another, he separated the sun and the moon because their arguments were preventing the crops from growing.

So whether you’re the kind of person who likes to play the tricks, or the kind who always falls for them, remember not to hit someone who gave you a yam. Especially on April Fools’ Day.