“Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound.”

Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird. It’s a plane. It’s Superman!

“Yes, it’s Superman, strange visitor from another planet who came to Earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men. Superman, who can change the course of mighty rivers, bend steel in his bare hands. And who, disguised as Clark Kent, mild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper, fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way.”

No hero has penetrated the American mainstream more than Superman. Yet despite this status, Superman does not share the same level of financial success in 21st century cinema as his counterpart heroes. Superman is too boring and too powerful, many will argue. He’s the corporate hero, clean-cut and idealistic, fighting for an arbitrary ideal of the American dream: “Truth, justice, and the American way.”

But Superman wasn’t always the stringent representative of American corporate culture. Kal-El of Krypton was once the representative of the underdog, the immigrant, and social justice. The Man of Tomorrow has long been a representative of the ideals of today, changing with the times to act as a reflection of our own perception of society.

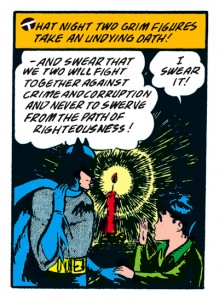

Superman, like many of the heroes who followed in his footsteps, was born of tragedy, both on the page and in real life. Brad Meltzer, author of The Book of Lies, theorizes that Superman’s creation is directly linked to his creator’s most tragic moment.

In 1932, a robbery led to the death of Mitchell Siegel. Whether his death was caused by a murder or a heart attack has never been fully clarified, but Meltzer believes this event led Mitchell’s son, Jerry, to dream of a man impervious to bullets and fearless of crime.

Jerry Siegel and his artist friend, Joe Shuster, were two poor Jewish boys from Cleveland. They first conceived of a “Superman” as a bald, telepathic villain, who more closely resembles today’s Lex Luthor than the Man of Steel. This quickly changed, however, and by the time the boys sold the first Superman story to National Periodicals, today’s DC Comics, Superman had become a hero, with traits taken from mythology, science fiction, and the immigrant experience.

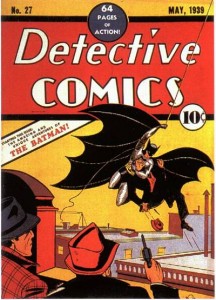

Action Comics #1 introduced Superman to the world in 1938. From the beginning, the traits that define the Man of Tomorrow were on display. The world’s first superhero fought off criminals, showcased his fantastic powers, and, as the lowly Clark Kent, fumbled his way with Lois Lane to begin a 75-year love triangle. This strange relationship between Kent, Lane, and Superman has been the focus of many stories across the decades.

The tragic relationship among these characters is representative of an idea that certainly must have existed in Siegel’s mind. As something of a geek, Siegel certainly believed he was more capable than anyone would give him credit for. If only the beautiful girls could see the real Jerry, perhaps they would like him. It’s a story that every kid who’s been called a loser can understand.

It was very much the man of Superman that appealed to fans. Comic readers have always been marginalized by society. The readers of Action Comics were primarily young boys, many of whom had been bullied in their lifetimes and could relate to the character of Clark Kent.

Borrowing from his father’s immigrant experience, Siegel wrote Superman as a visitor from a formerly great society, sent to a new world to live a better life. The planet Krypton was written as the old country, like the Siegels’ home of Lithuania. Upon arriving in the new land, Superman, like the immigrants of the day, changed his name from the Hebrew sounding Kal-El to the very Anglican, WASPish name, Clark Kent.

Superman’s origin story has often led to comparisons with the story of Moses, as both were sent away from their mothers to survive inevitable death and become a hero to the people. In time, the story has also been seen with many Christian connotations, most famously in the 1978 Superman film, with Marlon Brando’s Jor-El sending his only son from the cosmos to save the people of Earth from their own mistakes.

Christian stories were not the original inspiration for the creators’ work. Rather, Siegel and Shuster took inspiration from mythological heroes Hercules and Samson and from pulp heroes Flash Gordon and Doc Savage, while naming their hero’s base of operations, Metropolis, after the classic Fritz Lang movie.

Superman began life as a voice for Siegel and Shuster’s politics. Their hero fought against evil in all its forms, whether on the streets, in boardrooms, or in the nation’s capital. Siegel and Shuster’s Superman, years before becoming the representative of Eisenhower’s America, was the champion of social justice, unafraid to bend some rules to right terrible wrongs. Action Comics #1, in fact, sees Superman take on a corrupt U.S. senator, prompting the official’s confession by terrifying the man with a display of Kryptonian powers.

These powers were, at first, comparatively limited. In this first appearance, it was said only that Superman could leap one-eighth of a mile, hurdle 20-story buildings, outrun a train, with “nothing less than a bursting shell [able to] penetrate his skin.” It would be several more years before the Man of Tomorrow would take to the sky.

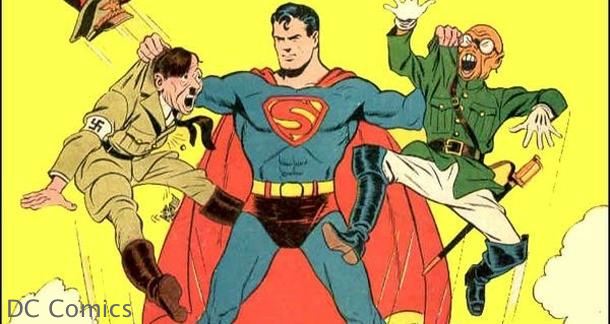

Action Comics #1 launched a phenomenon. Soon, everyone was releasing superhero comics. These comics remained popular throughout the War years, appealing to kids and soldiers alike. Symbiotically, the comics were also heavily influenced by World War II. With the existential threat of Nazis and Imperial Japan, the Man of Tomorrow became a patriotic hero to inspire American servicemen fighting overseas.

Unfortunately for the comics industry, popularity waned for the superhero genre in the years following the fight with the Axis. Superman, along with his eternal counterparts Batman and Wonder Woman, became the anchors of National Periodicals, pulling the company through the industry’s post-World War slump.

Superman did his part by dispersing his supporting cast across numerous titles. Superboy, which told the story of Clark’s teenage superheroic exploits, was launched in 1949. Jimmy Olsen and Lois Lane followed suit by starring in their own titles in the 1950s.

The superhero of the mid-century was different from the early Siegel and Shuster hero in more than just attitude. This Superman had been changed across several adaptations in different media to become the hero we recognize today. Some of the hero’s most enduring traits were actually just practical responses to real-world problems.

Kryptonite, debris from Kal-El’s home planet, was introduced in the Adventures of Superman radio program as a way to allow the actor portraying the hero to take some time off. Animators for the Fleicher Studios Superman shorts were the first to make the man fly, believing that a leaping hero looked poor in animation and that flying would simply be easier.

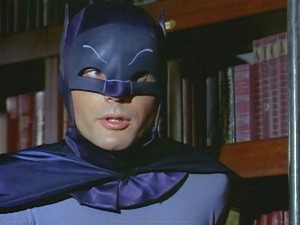

George Reeves brought Superman to life in the televised Adventures of Superman. To avoid the difficult question of how to make a man fly on camera, the producers decided to shoot Reeves either leaving or entering a building through windows to create the illusion of flight.

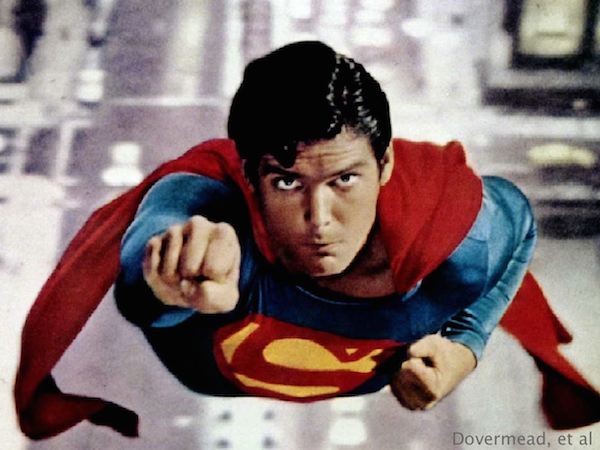

In 1978, Richard Donner and Christopher Reeve took the Man of Steel to the silver screen. Using new production techniques, the crew was able to simulate flight on film, allowing the movie to adhere more closely to the source material.

The movie was a huge success, with Reeve stunning audiences in his convincing portrayal of both the confident Superman and the perpetually terrified Kent. This success spawned three sequels and the 2006 homage, Superman Returns, directed by Bryan Singer and starring Brandon Routh.

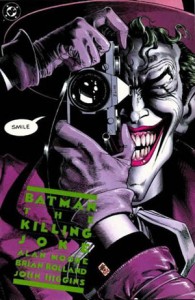

While movie audiences were enamored by the high-flying hero, comic fans were demanding more realism out of their heroes. In a daring move, DC rebooted its entire multiverse in the crossover comic Crisis on Infinite Earths in 1986. A “last” Superman story, based in the original continuity, was offered to his original creator, Siegel, but had to be turned down due to legal disputes over ownership of the character. Instead, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow was written by Alan Moore, and told the story of Superman’s final adventure as a hero.

This “final” story was followed by a new “first” story. Man of Steel, written by John Byrne, retold the origin of the hero. Kent became the primary identity, with Superman being the secret. Krypton was explored further, extraneous elements to the mythos were dropped, and all of the hero’s adventures as Superboy were erased. Clark was now a young man coming into his own, trying to understand his supernatural powers and dedicating his life to helping the people of Earth.

Kent soon returned to television in the hit show Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. The eponymous couple were the focus of the show, with superheroics as just an added element. The success was short-lived after a jump the shark moment when Lois and Clark decided to get married, killing the sexual tension that made the show popular.

The launching of Lois and Clark foiled plans to have the couple marry in the comics, and the writers were forced to delay the nuptials. Plans for the following year of comics had to be thrown out, and the writers decided on a bold new plan: kill the unkillable man.

Death of Superman is considered a landmark of comic book history. The book was wildly popular. Collectors bought issues with the expectation of an eventual return on their investment. That will likely never come to pass, of course. This being comic books, Superman remained dead for a mere eight months before returning, with a mullet, to fight the forces of evil yet again.

In the 21st century, the Man of Tomorrow has proven to be the Man of Today, finding success across several media. Smallville, launched on the teen-centric WB Network in 2001, told the tale of young Clark Kent in his decade-long journey to become Superman. The show was a success and humanized the hero in the eyes of fans new and old.

While Kent was finding success on the small screen, Superman was having a tough time on the big one. Superman Returns was financially successful but disappointed the brass at Warner Brothers who expected higher returns. In response, a sequel was aborted in favor of a reboot helmed by Watchmen director Zack Snyder. Man of Steel, released in 2013, again retold the story of Superman’s origin as an alien from a phallic-inspired space society who landed in the middle of Kansas — where human lives are apparently not as important as an explosive action scene.

Criticisms of Man of Steel aside, the movie was again successful at the box office and proved that Superman is still as marketable as ever. Superman will return to the big screen in 2016’s tentatively titled Batman vs. Superman.

Superman may be boring to some, but he sells comics and sells tickets. The Man of Tomorrow has endured across generations because he inspires us to strive for more. Sure, his level of perfection is unattainable, but the humility of this all-powerful alien warrior offers us an example to live by.

Superman may not bring in as much capital as Batman or Iron Man, but the hero from Krypton has always been about more than that. Superman is a reflection of our society. He reminds us that in our darkest hours, we can always look to the sky.