Fall doesn’t officially start until Tuesday, but the cooler temperatures in my part of the country over the past week prove that the change of seasons is definitely upon us. As I pointed out last week, the arrival of fall also means the arrival of fall television. Last week, I shared some of the returning shows I was happiest to have back on my screen. This week, I’ll take a look at the new series I’m looking forward to checking out.

I don’t tend to watch a lot of sitcoms as they air live. The Big Bang Theory and How I Met Your Mother were exceptions to that rule, and for each of them, I came in after several seasons had already aired. I’m a fan of New Girl, though I’m usually a season behind and watching on Netflix. Last season, I enjoyed The Crazy Ones, then was disappointed when the series was canceled and even more heartbroken when we lost Robin Williams last month.

This year, I am planning to give Selfie on ABC a chance — despite its annoying pop culture title. I have to admit, if the series wasn’t starring Karen Gillan and John Cho, I probably wouldn’t even consider watching … although the idea that it’s loosely based on My Fair Lady also has me intrigued. I loved Gillan as Amy Pond in Doctor Who, but she really impressed me this summer as Nebula in Guardians of the Galaxy. I can’t wait to see how she does in an American sitcom. Early reviews for the series have been really positive, so this may be a case of “don’t judge a series by its title.”

Speaking of former Doctor Who stars, the Tenth Doctor himself will be starring in Gracepoint on Fox this fall. Gracepoint is a 10-episode television “event” based on the British series Broadchurch. David Tennant will be reprising his role from the original series, this time with an American accent. The show centers on the investigation into the murder of a young child in a small seaside town.

Broadchurch was absolutely fantastic, and if you enjoy suspenseful crime drama, I highly recommend it. The cast and the writing were brilliant; it was easily one of the best series I watched last year. At first, I was disappointed to hear that Fox was making its own version of the series, and I was determined not to watch: there is no way they could even come close to the quality of its predecessor. But the casting of Tennant has made me curious, and I’ll willingly watch anything in which he appears.

According to Fox, the story will not play out exactly as the mystery in Broadchurch did. The writers have apparently changed the ending so fans of the original won’t know what’s going to happen. However, the trailers I’ve seen for the show so far make it look like the series was shot matching the original, frame by frame. Changes must have been made, though, to accommodate the fact that the American version is 10 episodes long versus the eight episodes of the British series. Hopefully, those changes do not lessen the suspense or drama that was so effective in the original series.

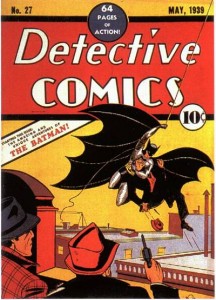

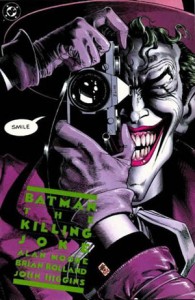

While Marvel has proved that it can easily dominate the box office, DC has seen a lot of success on the small screen over the years. This fall, NBC, the CW, and Fox will all premiere new series based on DC comics staples.

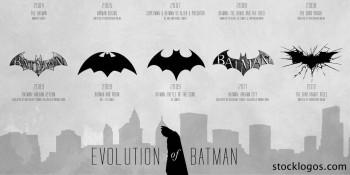

There has been a lot of hype and anticipation for Fox’s Gotham, which tells the story of James Gordon, the future police commissioner, prior to the existence of Batman. The series will also provide origin stories for many members of The Rogues Gallery. So great is the excitement for this series that Netflix has already acquired the exclusive rights to stream it after the episodes’ first runs. I tend to be skeptical of any genre show that Fox airs — not because I don’t believe it will be good, but because even if it is, there’s a high chance of Fox pulling the plug without really giving it a chance. The success of Sleepy Hollow last year, though, has given me some measure of hope.

Gotham will bring a talented cast into our living rooms. I’m particularly excited about Donal Logue playing Gordon’s partner. Logue has the ability to pull of great comedy or serious drama, and I’ve really enjoyed every performance of his that I’ve seen. I wasn’t a fan of The O.C. or Southland, so I know nothing of Ben McKenzie, who will be playing Gordon, other than that he’s more clean-cut than I was expecting. I’m really curious to see what he’s like. Lastly, a bit of trivia for the Doctor Who fans: Alfred, the butler for the Wayne family, will be played by actor Sean Pertwee, the son of the Third Doctor, Jon Pertwee.

Constantine is probably the series I know the least about but am still looking forward to watching. I’m not very familiar with the source character, beyond his appearances in the The Sandman comics and the Keanu Reeves film (or the knowledge that he inspired the look for Supernatural‘s Castiel), but I’m still intrigued by this series. Series star Matt Ryan certainly appears to have the look and attitude of John Constantine.

I haven’t heard much about this series over the summer, aside from the news that Lucy Griffiths‘ character, one of the main characters in the pilot, had been written out for creative reasons. I was a little disappointed by this news, as I’ve been a fan of Griffiths since she played Marian on BBC’s Robin Hood. Since I haven’t heard as much hype about Constantine as some of the other series on this list, my expectations for it are not as high. Of course, the lack of buzz also makes me a little more concerned about its fate at the network. (NBC doesn’t have a much better reputation than Fox when it comes to giving series a chance.) I also have a feeling my lack of knowledge about the comics will work in my favor, as I won’t be comparing it to the comics or criticizing certain creative decisions.

The new series I’m most excited about this fall is probably The Flash. I wasn’t sure about casting Grant Gustin as Barry Allen at first, but I could have been a little biased by his appearance on Glee. However, I really enjoyed his two-episode appearance on Arrow last season, and I am now looking forward to seeing what the show looks like. I’m also excited that it appears The Flash and Arrow will remain closely connected, as Stephen Amell has already confirmed his appearance in the pilot episode, and a crossover is set for episode 8 of each show’s upcoming season.

I’m also a fan of the rest of the cast, which includes Tom Cavanaugh, Jesse L. Martin, and the former Barry Allen himself, John Wesley Ship, as Barry’s father. Recurring cast members will include Robbie Amell, Stephen’s cousin and the star of last seasons ill-fated The Tomorrow People, and Prison Break‘s Wentworth Miller. The previews for the series so far have looked great, and I can’t wait for it to premiere. I just hope it doesn’t take as long to draw me in as Arrow did.

There are all the new series I’m most excited about seeing premiere in the next few weeks. What new shows are you looking forward to? Are there any here I forgot that you think are worth a mention (or worth checking out)? Leave your thoughts in the comments!