Recently on Fox Business Network, former New Jersey Superior Court Judge Andrew Napolitano showcased his historical contrarianism by attacking the most revered presidents in U.S. history, including Abraham Lincoln. The judge declared that the American Civil War was Lincoln’s fault: that slavery had been on its last legs and that Lincoln’s decisions actually set back progress by a century.

Napolitano is a well-educated man and obviously came to this opinion after actually studying the topic, but his assertions were not unlike those made by many students of history — at least the ones who don’t dig too deep. Napolitano’s opinions are not accurate, and more indicative of a personal bias toward skepticism. And while skepticism is healthy and good for debate, Napolitano’s limited and factually erroneous views of our 16th president show how a need to believe the worst in people can easily lead to missing out on the whole story.

Napolitano contended, in part, that “[i]nstead of allowing it to die, or helping it to die, or even purchasing the slaves and then freeing them, which would have cost a lot less money than the Civil War cost, Lincoln set about on the most murderous war in American history in which over 750,000 soldiers and civilians — all Americans — died…”

Napolitano’s comments are part of a troubling trend in interpreting the Civil War. In an attempt to seem open-minded and free-thinking, smart people are arguing against the grain. While these antithetical arguments sometimes bring out valid new perspectives, this view of Lincoln and the Civil War does not. Unfortunately, Napolitano is not alone in his “scholasticism.”

On a recent episode of Real Time with Bill Maher, the brash host showed his skepticism about lionized personalities as well by asserting that Lincoln was a racist. Maher’s guest, basketball great Kareem Abdul-Jabar, stood up for Honest Abe, just as Jon Stewart did against Napolitano. To his credit, Maher didn’t press Abdul-Jabar to reverse his position. However, the opinions expressed by Maher and Napolitano are shared by a lot of educated people who misunderstand Lincoln’s actions and ascribe sinister intentions and dark thoughts to one of America’s greatest heroes.

The problem is one of historical comprehension. Lincoln has been apotheosized in the nearly century and a half since his death. This deification is certainly deserved, but it also causes us to attribute superhuman traits to a real man — a man who faced great odds and triumphed. For those of us who study history, this idolization has caused a backlash.

When we see comments made by Lincoln in his pre-presidential Senate campaign debates with Stephen A. Douglas, we are shocked at their racist nature. When we hear about his desire not to end slavery but only to save the Union, we are hit with a gut punch, left wondering if there have ever been true heroes. Unfortunately, this is where otherwise intelligent men like Maher leave the conversation. The problem with this analysis of history, however, is that it only tells half the story.

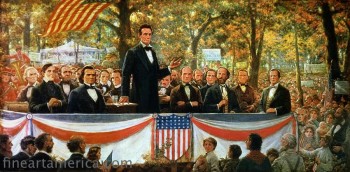

Let’s first look at Lincoln’s purported racism. The most frequently cited statement in support of the claim that the Great Emancipator was no better than the people of his time is from Lincoln’s debate with Douglas in Charleston, Illinois, in 1858:

I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, [applause] — that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.

Harsh. It’s easy to see why some view these words as evidence against Lincoln. But these must be viewed in context.

Lincoln was, before anything else, a politician and a legal scholar. And despite our current attitudes, being a politician is not inherently bad. Many political operatives have been able to use their manipulative abilities to do great things for people. Lincoln was one such operative, and he was using his skills as an orator and a debater to slowly move the center position of the argument about slavery closer to the position of the abolitionists’.

Lincoln learned in his legal career that, by not objecting to every detail of an argument, he could more easily win that argument by only clinging to the aspect that was most important. If he conceded the alleged inferiority of the African race and offered that intermarriage should not be permitted, his argument that slavery should be abolished would be viewed as the bare minimum argument, and therefore, the moderate stance.

The future president was also debating with the shining star of the Democratic Party. Douglas, known at the time as the advocate for popular sovereignty, was pushing his philosophy as a way to answer the difficult questions about the expansion of slavery. When states like Kansas applied for statehood, the U.S. Congress was left gridlocked in debate, time and time again, about whether or not slavery should be allowed there. Douglas’ answer was that the inhabitants of the state should be allowed to choose whether or not the “peculiar institution” could exist within their boundaries. At the time, that was considered the moderate position.

Lincoln had to run against this supposedly moderate man while wearing the label of “Republican,” a party which, at the time, was considered a radical and “black” party. Lincoln, like good politicians of today, had to play down his more “radical” viewpoints in order to appeal to a broader population. As such, he said things that could be construed today as anti-black and racist.

When answering Douglas’ charge about Lincoln wanting complete equality for “the negro,” Lincoln answered: “I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.” By stating his view this way, Lincoln was not saying that there was anything wrong with mixed race marriage — though it is doubtful he cared either way — but was instead making Douglas’ complaints seem absurd and out of touch. By changing the terms of the debate, Lincoln was making the abolition of slavery appear to be a more palatable proposal. Lincoln was nothing if not a moderate, and his political decisions and speeches reflect that.

At the time of Lincoln’s political career, one solution to the slavery problem that was advocated strongly by abolitionists was the colonization of American blacks in Africa. Lincoln supported this venture even through the beginning of the Civil War. This support has been seen by some as further proof of Lincoln’s racism. However, this is another case of not understanding context.

Lincoln’s statements were colored by what actions were politically and logistically feasible. His ideas were pragmatic, and abolishing slavery in the United States when the South held such disproportionate power would have been impossible. The colonization proposals were often made by men who wanted abolition, but who realized that unchaining thousands of men and women after lifetimes of brutality and oppression would lead to great civil unrest and, possibly, ethnic war. By simply removing the former slaves from the continent, the horrendous institution could be destroyed, and former slaveholders would not have to fear for their lives.

However, slavery was the backbone of the American economy, especially in the South, and not even the $3 billion it would cost to buy the freedom of the slaves would be able to persuade the men who profited from the blood and sweat of their fellow human beings. Again, Napolitano’s claim that Lincoln could have simply bought the freedom of the African race is completely off the mark, as the president would have been more than happy to perform such an action had it been possible.

Lincoln’s election as president in 1860 caused an enormous backlash from Southern reactionaries despite Lincoln consistently stating that he had intended to leave slavery alone. Lincoln, in fact, believed he was constitutionally bound to defend the institution despite his personal hatred of it.

“Honest Abe” was very much a constitutionalist and intended to follow the document according to his interpretation, even when he didn’t support what he believed it said. As a result, he promised to honor his duty — to citizens of both North and South, meaning that he had to follow even the laws he despised, like the Fugitive Slave Act. Since Lincoln did not acknowledge secession as any form of legitimate act, he considered himself to still be the president of even those states in open rebellion. And, as treason is a crime, Lincoln responded in the way his constitutional oath required of him.

The idea that Lincoln started the Civil War is absurd. With seven states already in active rebellion by the time he took office, Lincoln had to respond quickly and in a way that would give him the advantage. The first step was to simply wait for the Confederacy to become the aggressors. By sending federal aid to Fort Sumter, Lincoln was directly challenging the South’s claim to sovereignty. The Confederates fell for the trap, firing on the Fort, giving the Union the moral edge, and helping to rally Northerners who were still indifferent toward the secession.

Does this tactical maneuver mean that Lincoln should be implicated for starting the war? No. He was acting in a constitutional manner, doing the job he had sworn to do. The South was actively breaking the law through secession, and Lincoln, as chief executive, was responding. In fact, by waiting for the South to shoot first, the president was taking a much more lenient position than could have reasonably been expected.

Lincoln continued to move the country forward through his moderation. It’s true that the “Emancipation Proclamation” actually freed no slaves, but it didn’t have to; it is not as though its inability to be enforced makes it a less remarkable document. The proclamation, along with the more romantic “Gettysburg Address,” changed the war. It gave Southern blacks something to fight for by granting them freedom when the war would end. The proclamation may not have directly freed anyone, but it removed any doubt that the Civil War was about ending slavery — ironically causing the South’s fears to be realized. Further, it made abolition into a reasonable solution for more of the American population, which set the stage for the complete emancipation brought on by the 13th Amendment.

Napolitano’s criticisms of Lincoln are nothing new. It’s easy to take the Great Emancipator’s quotes out of context, like Maher did, and call Lincoln a racist. It’s easy to call Lincoln a warmonger when ratings or provocation are more important than the facts. But to do so is wrong.

Lincoln had a goal in mind and worked slowly toward it using the means available to him as president. By moving slowly, asserting the “moderate” view that the African race was inferior, waiting for the South to fire first, refusing to free slaves for the first few years, then technically freeing none, he opened up the possibilities for change that resulted in three powerful amendments to the U.S. Constitution, as well as millions of newly freed Americans. Lincoln’s actions changed the world for the better.

If you want to know more about Lincoln, read Gary Wills’ Lincoln at Gettysburg and Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals

, and watch Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln

. Pay special attention to the Cabinet meeting scene in which the president explains why a 13th amendment to the Constitution is necessary. That scene, and the movie on the whole, perfectly captures Lincoln’s moderate philosophy of governing.

“I leave you, hoping that the lamp of liberty will burn in your bosoms until there shall no longer be a doubt that all men are created free and equal.”

— Abraham Lincoln, July 10, 1858, Chicago, Illinois.