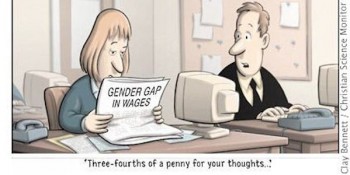

Today is National Equal Pay Day in the United States. The occasion marks the day on the calendar when the average American woman will have worked long enough since last January (463 days) to earn as much as the average American man earns in a single year. That puts the gender pay gap at 77 cents on the dollar, a place it startlingly has hovered around for the past decade.

Of course, there are voices in the wilderness that deny the pay gap exists, or attribute the gap to spurious causes. My blood begins to boil when when I read articles about the “wage gap myth.” One popular excuse for the pay gap contends that if women would just take more risks like men do, the gap would be eliminated. To that, I call bullshit.

I am not predisposed to be a crusader against the pay gap. My own experience during my formative years was quite the opposite. I grew up in a household that often bucked traditional gender roles. My mother worked full time and spent her evenings earning her college degree. My father worked full time as well; as a blue-collar laborer, he had the advantage of working set hours and being home every day by 4 p.m.

This meant that it fell on my dad to get me ready and shuttle me back and forth to ballet classes. I have a vivid memory of my father getting my hair into a slick bun and plastering foundation and bright red lipstick on me for my dress rehearsal of my second dance recital.

Eventually, my mom earned her degree (one semester after I completed mine). But growing up in this manner, I had a father who took care of the daily cooking and cleaning. That isn’t to say my mother was never around or didn’t contribute to the maintenance of the household. She never missed a soccer game, dance recital, band competition, or musical. But she didn’t have time to handle the day-to-day household work because she was working 50-plus hours each week in addition to attending night classes.

I tell you all of this because I think everyone will be able to deduce that my mother earns more than my father. There are a lot of men who, I think, would be uncomfortable with this reality. But then again, those men wouldn’t be caught dead braiding their daughter’s hair. So I was raised in a household where the wage gap wasn’t real, at least not in my limited worldview.

But then I entered the real world …

As I embarked on my professional career, I had a lot of things working against me. I graduated from college in December 2008, not long after the Bear Stearns collapse that signaled the global economy was on the brink of disaster. Most of my college friends delayed entering the workforce, either by picking up a minor or entering graduate school, because jobs were few and far between.

In addition to the cratering economy, I had also chosen a field where the big boys still ruled: the messy realm of politics. I took the job I could get at the time, as a secretary. I steadily worked my way through the ranks and became a research analyst, utilizing my skills to draft legislation and amendments. I was aided in that advancement by having the luxury of directly working for one of the least sexist people in the world.

After nearly five years of hard work and dedication, I was noticed by a few key individuals and was offered a position, unsolicited, at a lobbying firm. I was ecstatic. I felt like I had made up for starting my career behind the eight ball, had excelled in one male-dominated field, and was ready to take on another. I was finally going to be earning a great wage, and I would actually be out-earning my husband (who didn’t mind at all).

I took the job — but not without a lot of internal debate, because I loved my old job. In the end, I decided I wanted new challenges and the chance to add to my skill set. And then, after three months, I was miserable. I really disliked my job, and I dreaded going to work every day. Long story short, I resigned. Thankfully, my husband’s income and the pay I had been able to bank allowed me to leave a position that put me on the brink of a nervous breakdown.

While attempting to get a job back at my old place of employment, someone told me, “You know, it wouldn’t kill you to go back to being a secretary.”

This sentiment made me stop in my tracks. The unspoken implication was that, because I was female, I could just slip back into a secretarial role, be satisfied, and be grateful that I had a job. But to me, it would have felt like the five previous years of my career had been a waste. I was even told by one person that I wouldn’t be considered for any position higher than a secretarial one.

As an aside, let me say that I don’t think I’m “too good” to be a secretary. I was a secretary, and a damn good one at that, for almost a year. The job has many challenges, and I have worked with secretaries who could proverbially kick my ass in the skill sets specific to the job. But as a secretary myself, I was bored out of my ever-loving mind for a year. I hated the logistics of managing another individual’s schedule, finances, and mileage. I didn’t like balancing my own checkbook, and now I had two that I had to manage. Those women (and a few men) who are great secretaries seem to love what they do — and that’s great for them, but it’s just not for me.

I have often wondered: if I lived in a world where I had every advantage of being a man, how differently would my attempt to return to my job have played out? Before that, in spite of the economic downturn, would I have begun my career as a secretary? Would I have been treated differently at the lobbying firm?

Would anyone ever suggest to my husband that it wouldn’t kill him to spend a few years as a secretary? I doubt it. It’s these sentiments, straight out of Mad Men, that contribute to the gender pay gap.

I left a good job to try to get a great job. I took the risk that the wage gap critics are talking about, and it backfired. Oversimplifying the complexities of the gender pay gap into this one point, or any one point, is dangerous and myopic. There are so many factors that contribute to the wage gap, including race, nationality, socioeconomic background, and educational iniquities. Until we can have an honest discussion about everything that contributes to the gender pay gap, we will hover around 77 percent for decades to come.