Late spring into early summer is the perfect time for weddings. The weather is temperate and docile, the foliage is in full bloom, and potential guests have extra gift money on hand from low utility costs over the last few months.

Of course, wedding vendors the world over are well aware of these truths, and price accordingly. Between paying top dollar for the dress, the rings, the food (and cake), the venue, and the entertainment, somebody’s coming out of this process wishing it were December instead. It can’t all be lush, red roses and gorgeous, photogenic rainbows after all.

Let’s see if we can trim the fat a bit by looking at our cash-intensive traditions and where they come from. Maybe there are some things we can do without.

The Dress

What’s the deal with these wedding dresses, anyway? You buy one for way more than the price of any other dress you will ever own, and then you wear it one time ever. Whose bright idea was this?

As usual, we can blame Queen Victoria. When she married Prince Albert in 1840, she bucked the trends and picked white as her color, to signify purity. Shortly thereafter, it caught on, with rich women wanting to show off that they could afford a dress that would pretty much immediately be ruined if it suffered any wear or if they did any kind of work.

Most everyone does white these days, but it’s not required if you’re getting remarried (for whatever reason). In India, however, brides wear anything but white, as that’s the color of mourning, and typically go for red instead.

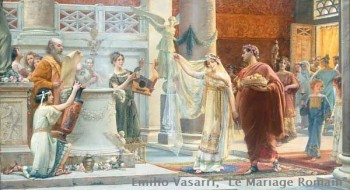

As to veils, these aren’t for hiding the bride’s beautiful face from the groom, but rather from evil spirits. Roman brides, along with their five witnesses (bridesmaids), wore veils and identical dress so as to confuse the dastardly spirits that might want to steal away her fertility at the moment she passes from the protection of her father to that of her husband.

When it comes to the bride adorning herself with something old, new, borrowed, and blue, this superstition seems to be related to protecting oneself from the evil eye. The evil eye, wielded at times even by an unknowing practitioner of the dark arts, is a widespread cultural myth, which in our contemporary society has been diminished to the less-malevolent “stink eye.”

Anyway, it was common practice for everyone to have something blue on them, to avoid the curses of the eye, which might cause things to dry up (like wells or, in the case of weddings, reproductive organs). The “something borrowed” really should, by tradition, be the undergarments of a woman who has already given birth, so they can confer her fertility to the new bride. We also typically leave off the final line of the poem, “and a silver sixpence in her shoe.” Silver, of course, doubles as a powerful aphrodisiac (not really) and werewolf deterrent.

The Rings

The first engagement rings were probably invented by the Egyptians, while the Romans made them popular. Roman men wore rings of iron to indicate that they were citizens. Giving such a ring to a bride-to-be would indicate that she was now “like people.” Romans believed the left ring finger (named after, y’know, where you wear your wedding ring) contained a vein (or sinew) that led straight to the heart. This idea is either delightful or creepy, depending on your perspective, I guess.

The Cake

More Roman origins. These Romans are popping up everywhere, I swear. In ancient Rome, the priest class, known as Flamen, got married by eating a cake made of spelt, a kind of wheat, in a ceremony called “confarreatio,” which basically means “eating spelt.” In medieval Europe, cakes were stacked up high, and if the bride and groom could kiss over their cake, they would have a long and happy marriage. Sucks to be short, I guess.

The Entertainment

In the United States, we hire a DJ or a band and get a second cousin who plays the viola to perform at the ceremony. Then people dance, or not, as the mood takes them. We have first dances, parental dances, money dances, ridiculous group dances like the Chicken Dance, Electric Slide, Macarena, the Hora if you’re Jewish, that terrible clapping, stepping, cha cha thing, and I’ve even seen the Hokey Pokey once or twice. Maybe some other cultural traditions can help us out here, to give us some more variety, at least.

In Ethiopia, the wedding day starts with the groom and his friends going to the bride’s house and forcing their way inside through the bride’s relatives while loudly singing. The “best man” then sprays perfume everywhere inside. Why yes, yes, it is an overt metaphor for sex.

How about Germany, where bride kidnapping is the norm, which you may recognize from The Office. The groomsmen take the bride bar-hopping, leaving clues behind, while the groom follows after them and pays their tabs. Hmm … that doesn’t really sound less expensive than the overpriced DJ.

In Romania, the lăutari (“lutists”) follow the couple around all day, playing specific songs to fit the moment, and act as entertainer/emcee/event organizer all in one.

The Ceremony

In the United States, the ceremony is most often going to be a Christian one, performed in a church. We have special music, ring exchanging, vows, probably a brief sermon, and then people throw rice at the married couple. Also, there are unity candles these days. What is the deal with those, anyway? Like, people aren’t content with the half-dozen existing symbols for unity inherent in the wedding service, like the rings, the joining of hands, the kiss … they also need something that’s blatantly called a “unity” candle? I’ll get over it.

Maybe you’ve also seen a Celtic-style rite called handfasting? The word “fast” comes from Proto-Germanic fastuz (“firm”). We have three definitions for the word, which carry very different meanings, but they all happen to share this root. You can be a fast runner (or a “firm” runner). You can fast to skip meals or other desired things (or hold “firm” against temptation), then break your fast by eating breakfast. You can also fasten two things together, which is the meaning implicit in handfasting. The rite involves wrapping a hand each of the bride and groom together with cloth to symbolize, you guessed it, unity.

You might also have been to a Jewish ceremony, which has a chuppah (Hebrew: “canopy”), a sheet, held up by four poles, that’s spread over the couple when they get married. It symbolizes the home they’ll build together. A Jewish couple would also then sign a ketubah (Hebrew: “written thing”) outlining the responsibilities of the groom toward the bride.

Hopefully, if nothing else, this article can show potential brides, grooms, and payers of the wedding expenses that there are abundant options available to them, whether or not some would be particularly advisable/accessible in your locale, or defray the costs versus the norm even if they were.

So, cheers, everyone. Keep on marrying and giving in marriage. I’ll see you next week.