Call me nosey.

I’ve been called worse. But when I happen to be at a bar by myself, I tend to survey the scene. I’ll peruse the beverages on draft and look to see which bartender is apt to provide the best service, but, mostly, I’ll eavesdrop and “people watch.”

Recently, I overheard a college-aged man and woman, seemingly on a date for only the first or second time, sitting at the corner of the bar. Nothing unique, really, but I got the sense early on that the young woman was either not much of a drinker or had recently turned 21 and had little beer-ordering experience. She asked her date to order for her because she didn’t know what to get. He asked her simply, “Well, do you want an ale or a lager?”

I wasn’t listening intently — I’m not that nosey — but the question piqued my interest because I immediately thought to myself, “Come on, kid, do you really think she knows or even cares about the difference?” Not to my surprise, she just stared at him blankly and shrugged.

Now I was listening because I was wondering how this guy would explain it to his date. Obviously, a cold scientific response would not work and would more than likely bore his date to tears. “Budweiser is lager,” he started, and then he paused as he scanned the available beers on tap until he found a green handle and pointed it out to his date, “and Sierra Nevada is ale.”

While I knew his answer was as vague as vague could be, he was essentially correct. His date shrugged again, still a perplexed look upon her face, and said she’d just have a Bud Light. (She added the phrase “I guess” afterward, further cementing the fact that his response meant nothing to her.)

So why the Bud Light and not the Sierra Nevada Pale Ale? Did she really prefer lager over ale? Or did the name have something to do with it?

Be honest with yourself: whether you’re a 21-year-old woman or a 45-year-old man, you are apt to begin considering which beer to order at a bar based on brand name. You, too, likely scan the bar taps, with their ornate, colorful, creative handles, making a mental checklist, crossing off the brands that don’t appeal. But there are many factors beyond the brand that can help you make your choice.

At its most basic level of contrast, beer can be broken into two main categories: ale and lager. You are most likely not going to order a beer by telling the bartender you just want an ale or a lager (unless, of course you’re in Pennsylvania, where “lager” is synonymous with Yuengling Traditional Lager).

All beer is made from the same basic ingredients: water, barley, malts, hops, and yeast. Other things may be added in to influence flavor, color, or consistency, but those elements are common to all beer. The difference between an ale and a lager can’t be found in most of those ingredients, either: some ales will use the same type of malts and hops in their beer as a lager counterpart.

So what is the difference in the name? What makes ale ale and lager lager?

While there is no doubt that some exceptional and seasoned beer drinkers will claim to be able to pinpoint very different tastes between lagers and ales, it really comes down to one thing: the type of yeast used in brewing.

Ales have been brewed for much longer than lagers, with some ancient recipes of ale as medicine having been discovered to date back as far as Sumerian times. Ales most commonly utilize a yeast called Saccharomyces cervisiae, which has been cultivated for thousands of years and which favor warm temperatures, usually between 58 and 86 degrees Fahrenheit. These yeast strains must be brewed at a warmer temperature because, if the water is too cold, the yeast become dormant and do not naturally ferment to turn the water into beer. Most wine production also uses S. cervisiae or a similar strain of yeast.

S. cervisiae is also a top-fermenting (or top-cropping) yeast, meaning that as the brewing occurs, the yeast floats to the top of the brew tank and settles over the beer. This allows for a thick, frothy foam to form over the ale. Ales brewed in this method tend to allow for the fruit and bitter aromas in the hops to be overt in the finished product. Because of this, some ales will have a much cloudier appearance than lagers. Unless very stringent filtering techniques are utilized, most ales will have noticeable remnants or sediment from the yeast even when bottled.

On the other hand, lagers are cited in references and recipes only dating back as far as the mid-1500s in Germany and other parts of Europe. Lager uses a hybrid strain of yeast called Saccharomyces pastorianus, named after famous researcher Louis Pasteur, or Saccharomyces carlsbergensis, named by Emil Hansen, a researcher who worked for Danish beer giant Carlsberg Brewery in the 1800s.

Even though lager yeast is known by two names, it was later found that they are the same exact strain of yeast. Hansen discovered that his strain of yeast could be cultivated in-house and was easier to brew, needing less attention from the brewmaster’s watchful eyes. The owners of Carlsberg shared their secret of cultivating the lager yeast to all the big beer producers of the world, and mass-produced beer has been dominated by lager ever since.

S. pastorianus, while sharing some genome traits with S. cervisiae, grew to become a larger and more resilient yeast strain. The lager yeast also stays active when brewed in colder temperatures. Because of its size and its amenability to cold water, the yeast allows for what is known as bottom-fermentation (or bottom-cropping); the yeast gradually sinks to the bottom of the brew tank, leaving a clearer, cleaner beer.

Another decidedly different factor between ales and lagers is that lagers take much longer to brew. Most lagers need one or more months to ferment, whereas ales can typically be successfully brewed in as little as seven days. The name lager, in fact, is based on the German word lagern, which means “to store.”

It’s no coincidence that cold-brewed lagers are also often served ice cold. (After all, according to the commercials, a Coors Light isn’t fit to drink unless it’s cold enough that the mountains on the can turn icy blue.) Ales, on the other hand, especially those brewed under traditional circumstances like those in England and Belgium, are often served at cellar temperature, or around 55 F.

Let’s revisit the young woman at the bar with her date. Is it a shock that she chose Bud Light, a lager, when given the many choices at the bar? Could the popularity and familiarity of the Budweiser line of mass-marketed beers have played a part?

Nearly every popular American beer brand is headlined by a lager beer. In order for these beers to be produced at a high volume and at a low cost, most are what are known as American adjunct lagers. The word “adjunct” refers to the fact that many of the well-known lager beers (Coors, Budweiser, Pabst Blue Ribbon, Corona Extra, Miller High Life, and Foster’s) are brewed with an added grain, usually rice or corn, to round out the brew. The result is a beer that is usually very easy to drink: crisp, light in taste, low in bitterness, and with a pale yellow color and a middle-of-the-road alcohol level.

Many of the former flagship beers of the biggest macrobreweries have been supplanted by their “lite” versions. Light beers like Coors Light, Miller Lite, and our young lady’s choice, Bud Light, are also lagers. They are usually “lightened” by adding high volumes of rice or corn in the adjuncting process, thereby lessening the contributions, both in flavor and in calories, of the other ingredients. Light beers typically sacrifice those flavors for a lager that is much less filling.

The other popular form of lager in the United States is the pale lager, or pilsner. You’ve probably had world-wide marketed European pale lagers in the form of Heineken, Amstel, Stella Artois, and Harp.

Ales, on the other hand, are often the main attractions for micro and craft breweries. Ales tend to have much more robust, full-mouth flavors that linger. They utilize heavy amounts of hops and/or malts to achieve varying expressions of aromas and flavors. As a result, there are many styles of ale.

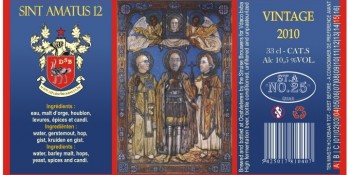

There is the American pale ale, like the one offered by Sierra Nevada. Pale ales and witbier are light and fruity, while the famous India pale ale, adored by hopheads across the land, packs on the hops to create intense floral and citrus aromas. Stouts and porters are ales that utilize heavily toasted grain to create a near-black ale with roasted malts and coffee overtones. Tripel ales up the yeast amounts, and quadrupel ales take it a step further by multiplying the grain ingredients four-fold to create dark, frothy ales high in sugar and malts, with equally high levels of alcohol.

But the types of ales don’t end there, with most styles being categorized by their place of origin. For example, there are English brown ales and Belgian brown ales, each having their own distinctive tastes and brewing styles. I could go on, as the number of ales is almost overwhelming … so go out and try some for yourself!

I recently took my own advice and pitted some pale ales against some pale lagers and pilsners. Here are my thoughts:

- Left Hand Brewing Company’s 400 Pound Monkey I.P.A., an India pale ale from Longmont, Colorado — Big, frothy head on this hoppy pale ale, notes of clove, coriander … just a lot of spice going on here, maybe too much. I give it a B-minus.

- Bell’s Brewing Company’s Lager of the Lake, a pale lager from Kalamazoo, Michigan — This pale lager is not all that impressive; it’s typical for the style, tastes like Miller High Life, only with a little more bitter aftertaste. C+

- Erie Brewing Company’s Mad Anthony’s A.P.A., an American pale ale from Erie, Pennsylvania — Easy-drinking … smooth, with a very tolerable amount of bitterness. Would make a good “everyday” beer. B+

- “Beer Camp” Electric Ray, an India pale lager that is a collaboration from Sierra Nevada Brewing Company and Ballast Point Brewing — A cool creaminess factor on this lager that is more ale-like, but with a crisp finish and a mild level of bitterness that slides from the taste buds, not destroying them; definitely unique. A

- D.G. Yuengling and Son’s Premium Beer, a pilsner from Pottsville, Pennsylvania — Note that this is not the famous Traditional Lager, but the “house beer” at Yuengling. A pilsner with a subtle level of hops that creates a crisp, cutting finish, with a refreshing carbonation. B

Nothing against the good people who produce Bud Light, but please don’t follow the same path as our young lady friend by choosing a beer based on its familiar name. Try some variety! Order a distinctive type of lager and an equally original ale, then rate them against one another until you find a favorite. That way, should you ever get asked the lager-or-ale question, you’ll be ready with an educated response.