Reading books has always been one of my favorite pastimes. One of the most positive aspects of my own childhood was having a variety of books at my disposal. Someone, usually my grandmother, would see that I got to the library every two weeks during summer breaks, and I could borrow as many books as I could carry. On my birthday, Easter, and Christmas, I could expect to receive many books as gifts.

Not only did I have access to books, but I also had good reading role models. My grandparents always spend their evenings reading. My grandfather favors nonfiction, especially political analyses and biographies. My grandmother prefers mystery novels.

My dad spent many hours reading to me as a child. I loved how he would change his voice for each character. He has always spent days when it is either too hot or too cold to be outside with a book in his hands. He especially loves Larry McMurtry and historical fiction set in the time of the fur-trading mountain man.

In the summers, I would spend some weekends with my aunt and cousin. My aunt would usually take us to the public pool and, when we were tired of the water, we would rest on her big blanket and listen as she read us The Hobbit.

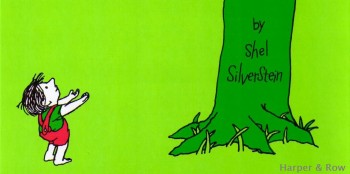

For myself, I prefer novels and historical fiction, though I do read nonfiction and biographies on topics and people who interest me. Long before I had kids, I knew that I would want to develop in them a love of books and reading. When I was expecting my first child, many books were given to me as gifts. Among them were classics from Beatrix Potter, plus Goodnight Moon, Where the Wild Things Are, whimsical books by Eric Carle and Sandra Boynton, and Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree.

For the beginning part of my first child’s young life, most of our time was spent with short and sweet books made out of fabric or board, which could survive near-constant exposure to baby gums and baby drool. But, after a while, I thought we’d read The Giving Tree. Everyone I knew said they loved it.

So, we began to read. The book starts out well enough. A tree loves a little boy. The little boy loves the tree. He loves her shade and her leaves and her apples. He loves to spend time with her, climb, swing, and play with her. The tree is happy. The boy is happy.

And that’s where the nice story ends and the personality disorders of the two main characters are revealed.

The boy grows up and leaves the tree but returns as a young adult. The tree invites the boy to come and play, but the boy says he wants to have fun and buy things and asks the tree for money. This is red flag number one: selfish freeloader. The tree doesn’t have money, of course, but gives the boy, now a young man, all of her apples to sell. The boy does not even say thank you. So far, the tree seems to be a helpful friend, willing to give the boy the benefit of the doubt that he really isn’t a selfish freeloader. The tree is wrong.

Years go by and the boy comes back to the tree. He is sad. He again refuses the tree’s offer to play and, without so much as a “How do you do?” asks for a house. Red flag number two: narcissism. Narcissism is a personality disorder in which an individual pursues personal gratification without regard for the feelings of others. Some traits of narcissists include (but certainly are not limited to) difficulty maintaining satisfactory relationships and a lack of empathy.

Of course, the tree has no house, but she does have branches, which she gives the boy (who is now a man) in order to build himself a house. He takes the lumber and leaves, again without saying thank you! The tree is happy.

Here’s where I begin to worry about this tree, because I’m pretty sure this tree suffers from codependency. Codependency, as defined by Wikipedia, is “a psychological condition or a relationship in which a person is controlled or manipulated by another who is affected with a pathological condition (typically narcissism or drug addiction); and in broader terms, it refers to the dependence on the needs of, or control of, another. It also often involves placing a lower priority on one’s own needs, while being excessively preoccupied with the needs of others.”

The tree now has no branches, no leaves, and no apples. It’s basically alone and naked in the woods for decades when the boy, who is now a much older man, comes back. I imagine him, during this absence, having been married and divorced a minimum of three times. He probably has foreclosed on at least one house and has developed a gambling problem and an addiction to alcohol and/or street drugs. He also has had difficulty keeping a job and is estranged from all of his kids because he never really cared enough to parent them.

But return to the tree he does, and the tree is ecstatic. Did he come to thank the tree? Did he come to visit, reminisce, or play with the tree? The answer, predictably, is a big, fat NO. Now, this guy whines that he’s too old and too sad and too miserable, and he wants to sail away in a boat. (Probably to escape those persistent debt collectors and the attorneys of his three ex-wives!) The tree offers her entire trunk to this self-centered bastard and is happy about it. If I was unsure whether the tree was codependent before, I’m not anymore. The man is not too old to carry away the rest of this tree, and he presumably makes his boat and sails away. I’ll let you guess whether or not he said thank you.

Finally, when the man is old and very near death, he comes back to the tree. The tree is actually sorry that she has nothing left to offer the man except what little remains of her stump. But he uses the tree one last time as a chair, and the tree is happy.

Really!?!?!

I hate this book because it’s not a story of love and friendship. It’s not even a story about giving, as the title implies. The Giving Tree is actually a really sick tale of a horribly dysfunctional relationship. For kids.

No, thank you. If my kids are going to learn about dysfunctional relationships, it’s going to be the old-fashioned way: by watching inappropriate movies and television shows, and by the example set by their dad and me.