A few weeks ago, I broached the subject of marital name change from a feminist point of view. I was surprised by how many of you weighed in on the subject, either in the article’s comments section or on various Facebook shares.

That was great, because Curiata.com was created to be a platform for its writers and readers to interact, discuss, and cultivate their opinions and tastes on many different things, from politics to superheros to recipes. There were a lot of excellent points raised in the subsequent discussions, and I wanted to take the opportunity to respond or expand on these thoughts.

First and foremost, one person felt that my column left the reason I decided to change my name unclear. As I said then, the real reason for my article was to highlight that it didn’t matter why I changed my name. The real feminist victory is that I had a choice; I was not forced or coerced to do anything against my will. But it got me thinking about nailing down a more precise answer for why I made the decision I did.

Several other commenters questioned if changing my name was a reflection of a lack of connection to my blood relatives. Some of my own friends have experienced a situation such as this and were happy to adopt their husband’s name for this reason. But for me, it wasn’t a lack of identity, but rather too many identities from which to choose. Let me explain — and no, I do not suffer from multiple personality disorder.

If you look at the surnames of my four grandparents, they are, in no particular order: Goodyear, Kimmel, Zellers, and Reynolds. I am no more or less any one of these names. As a matter of fact, I’ve often been told that I am a younger version of my paternal grandmother (which is odd, because she died when I was only two years old — very little time for her to have a significant impact on my life).

Her last name was originally Kimmel. So because I am similar to her, does that mean that my last name should be Kimmel, because I can identify with her? Maybe so, but in our current setup of naming, we don’t get to choose for ourselves until long after we’ve established an identity. And I inherited my father’s name, who inherited his father’s name, and so on and so forth all the way back to Saxony, Germany, when the original spelling was “Gutjahr.” I can also trace my mother’s family all the way to the 1600s in Ireland.

I don’t suffer from a lack of familial identity, but rather an abundance of it. Before I had finally decided to take my husband’s last name, I watched him trace my ancestry quite diligently. (In fact, I think he was more interested in my roots than I was.) When we linked our family trees, it was a huge patchwork quilt.

My husband is equal parts Hillman and Blackwell, Daley and DeMartine. He didn’t get to choose the surname Hillman, just like I didn’t get to choose the surname Goodyear. But the beauty of society in 2014 is that I do get to choose whether or not to change my name at an important juncture in life — when I begin a new family with my husband.

I would be lying to you if I said I’ve always loved my maiden name, Goodyear. But it’s not because I’m ashamed of or estranged from my parents or other ancestors who bear the name. In middle and high school, I was overweight. It doesn’t take too long or too much creativity for the blimp jokes to start rolling in. Intellectually, I understand that kids will be always be cruel, and I would have been picked on no matter my last name. Nonetheless, my maiden name still carries negative childhood connotations, and I’d rather not pass along this particular demon to my kids.

In fact, that brings me to the more precise reason I did decide to change my name: for the benefit of any future offspring my husband and I may have. I realized that by getting married, we were starting a new, unified family. And that someday, we hope to raise a couple of sensible feminists and/or modern urban gentlemen. I felt it was important to signify to the outside world that we are a team.

To that end, there was a brief moment in time when I toyed with the idea of combining our names to create a new name. The best I could come up with was Hillyear or Goodman. Neither of us was thrilled with either option, and after working so hard to trace our ancestry, it seemed a bit of a waste to start a brand new lineage with us. And since our tradition says that our children will inherit their father’s name, it made sense for me to make that change.

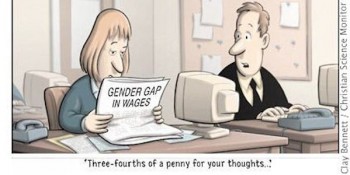

In reality, I understand that there will always be individuals who criticize any decision I make. If I would have kept my maiden name, there would have been individuals who felt that I was being disrespectful and emasculating to my husband. Since I changed my last name, I’m sure there are people who think I am “not feminist enough.”

If we would have opted to combine our last names, there are people who would say that we were being too politically correct, or my personal favorite, they would call us “damn hippies.” Lastly, if Mike would have taken my last name, he would have been mocked mercilessly by some of his male friends and coworkers; I also probably would have been called some interesting names if I had “forced” him into this.

I came to the decision to change my name on my own terms. I’m no longer forced, by law or by society, to take my husband’s name as a sign that I am his property. But not everyone has that level of comfort, and many would be judged cruelly if they make a decision that isn’t popular with the majority.

All of this is a long way of saying: yes, we have come very far in terms of the marital name change. But we still have a long way to go.